Zhemchug house is one of the key symbols of seismic modernism in Tashkent. Built as an experimental residential project using expanded clay concrete, it stood in stark contrast to the standard Soviet architecture of its time. Below, you’ll learn how this distinctive building in the capital of Uzbekistan was conceived, transformed over the decades, and what it represents today.

On April 26, 1966, a powerful earthquake struck Tashkent, leaving hundreds of thousands homeless and destroying millions of square meters of housing. From 1966 to 1969, the entire Soviet Union mobilized to rebuild the city, followed by an ambitious phase of development that introduced new palaces, museums, and even a metro system. After constructing an initial wave of 4- to 5-story buildings, city planners set their sights higher, commissioning architects to design 9- and 16-story structures capable of withstanding future seismic events.

In 1973, at the Tashkent Zonal Scientific Research and Design Institute for Standard and Experimental Design of Residential and Public Buildings (TashZNIEP) - an institution specializing in sun-protective architectural solutions for hot climates across the USSR - architect Ophelia Aidynova proposed a bold new concept. She envisioned a monolithic residential building with intermediate sections where every three floors would include a communal recreation area. Her idea drew inspiration from Japanese architect Kiyonori Kikutake, who sought to create high-rise buildings that compensated residents for being cut off from everyday life on the ground. A comparable approach was taken in Israeli architect Moshe Safdie’s Habitat 67, which gave each apartment a private garden. While Habitat focused on individual outdoor spaces, Aidynova’s project envisioned a shared courtyard for every cluster of 24 apartments.

In 1974, Aidynova encountered resistance when the chief architect of Tashkent initially refused to approve her proposal. Undeterred, she presented the project in Moscow, where it was also initially rejected. Yet through persistence, she succeeded in securing approval for the experimental monolithic high-rise. Construction began the same year - and continued for 11 years. One major reason for the delay was the construction team’s lack of experience with monolithic high-rise techniques. Some residents displaced by the demolition of earlier buildings on the site opted to relocate elsewhere before the project was completed. Zhemchug house was finally finished in 1985.

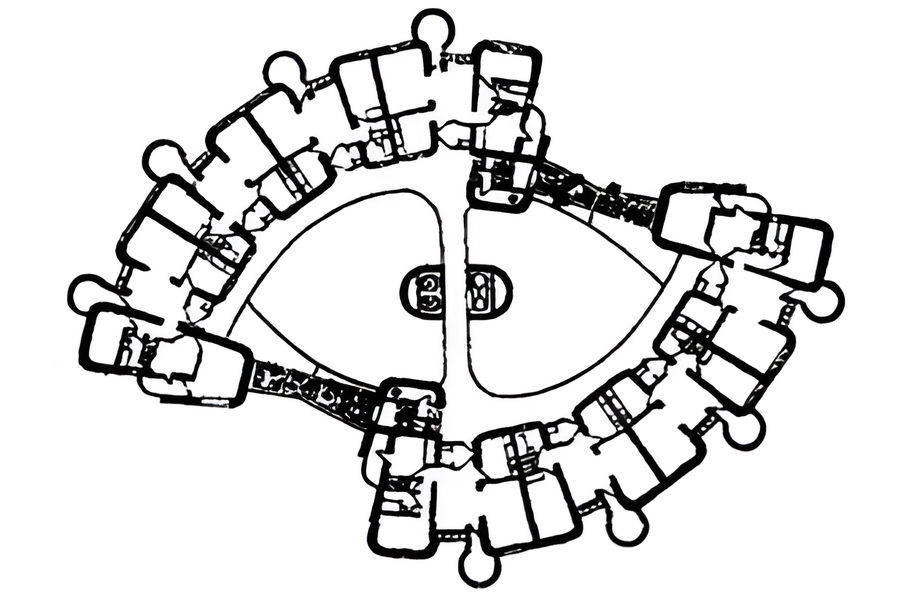

The Zhemchug residential building stands as one of the final landmarks in the era of Soviet seismic modernism in Uzbekistan. Its architectural form consists of two semicircular towers that converge at a central support column housing the elevators. Located on the 2nd, 5th, 8th, 11th, and 14th floors are open, 10-meter-high inner courtyards. To reduce the building’s weight and allow light to filter through, the ceilings of these courtyards are punctuated with numerous round openings. The structure is entirely built from expanded clay concrete, a material valued for its lightness, thermal insulation, and durability. The rounded towers resemble the vertical blades of a wind turbine - a design that encourages steady airflow through the open courtyards, providing natural ventilation ideal for Uzbekistan’s hot climate.

As envisioned by Ophelia Aidynova, the five courtyards at the heart of Zhemchug house have become vibrant communal spaces. Children ride bicycles and play games, while older residents sit on benches and chat. In earlier years, these spaces hosted holiday celebrations and wedding feasts. Each courtyard has its own unique layout and features a variety of trees and plants, enhancing the building’s connection to nature.

As part of the original design, a communal laundry room was installed on the first floor for all residents, though it was never widely used. Also on the first floor, facing the main façade, spaces were designated for workshops and a separate unit for a jewelry store, which for many years was considered one of the best in Tashkent. The store was called “Zhemchug” (Pearl), and it was this boutique that gave the entire building its distinctive name.

The roof of the building also featured experimental ideas: another recreation area was arranged here, along with a children’s pool. However, the pool was eventually closed due to water leakage into the elevator shaft. Several years later, in independent Uzbekistan, entrepreneur Ilkhom Karimov transformed the rooftop space. He renovated the area to create a venue for business and creative events. On weekday evenings, it hosted training sessions and seminars, while Fridays were reserved for music concerts. He repurposed the former pool into a decorative pond with goldfish. Today, the roof of Zhemchug house remains a private space, accessible only to club members and residents.

After the first residents moved in in 1985, it became clear that the innovative Zhemchug building had its shortcomings - residents jokingly called it a “survival experiment”. Apartment windows were designed to open horizontally, but most people quickly changed the frames to open vertically. The open balconies were gradually glazed. Each of the 120 apartments had one rounded wall, and although specially made furniture was provided to fit the curve, few residents liked it and ended up replacing it with regular furniture. The building’s deep, 6-meter basement was constantly flooded and was eventually filled with concrete. The waterproofing on the rooftop children's pool turned out to be poor. These were just a few of the many small things that residents had to change or get used to.

During the Soviet era, 20 high-rise residential buildings were constructed in Tashkent; today, dozens more are built every year. But only Zhemchug has become a true architectural monument, one of the few residential buildings in the city that can be considered a landmark. Its unusual design has long attracted local youth and tourists, and over time, residents grew tired of the constant attention. Today, the entrance is closed, and a fee is charged to visit. In this way, Zhemchug house has unintentionally become a museum.