Chinese literature has reflected the thoughts, struggles, and aspirations of countless generations, illuminating the philosophical depths that have shaped one of humanity's oldest continuous civilisations for over three millennia. From inscriptions carved into oracle bones to digital novels read on smartphones across the world today, this literary tradition reveals what it means to be human across time, offering travellers and culture enthusiasts a profound portal into the heart of the Middle Kingdom.

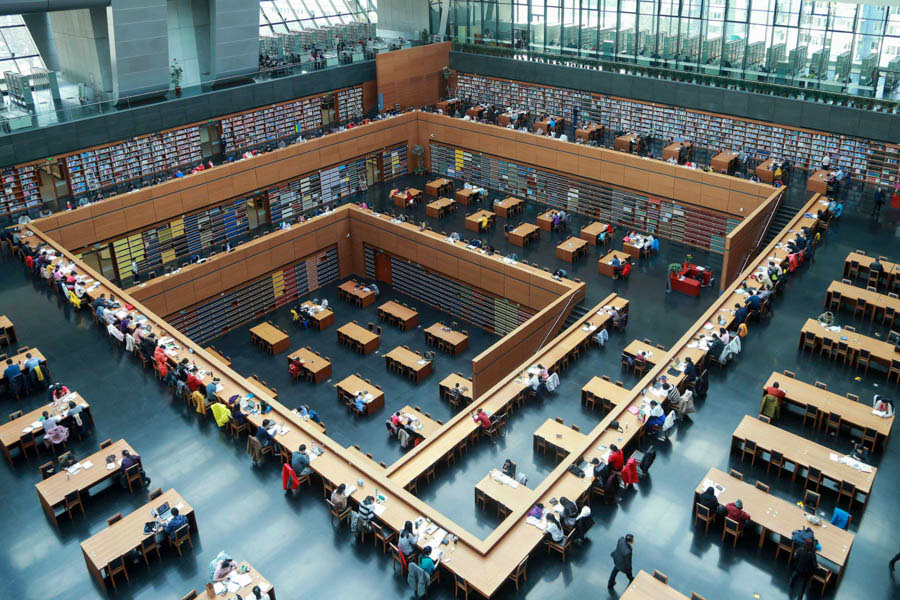

Breathe in the scent of aged paper through ancient scrolls in Beijing's National Library or take your seat in a traditional opera house as performers bring Journey to the West to life through gesture, music, and painted faces that transform actors into deities and mythological creatures before your eyes.

Early Chinese Literature: From Oracle Bones to Classical Poetry

Walk through the oracle bone exhibition at Beijing's National Museum of China, and you’ll encounter the earliest known Chinese writing. These fragments – over 150,000 (often cited; estimates vary) discovered since 1899 – bear writings carved into turtle shells and ox bones during the Shang Dynasty, roughly 3,600 years ago. Ancient diviners would etch questions about weather, harvests, and royal affairs, then heat the bones until they cracked, interpreting the fractures as messages from heaven. Stand close to these display cases, and you’re witnessing humanity’s earliest conversations with the divine.

The Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BCE) elevated writing from divination to philosophy and art. The I Ching (Book of Changes) offered wisdom on morality, governance, and the patterns underlying existence. The Shijing (Book of Songs), compiled around 600 BCE, preserved 305 poems, ranging from folk songs to court rituals, capturing voices from peasants lamenting tedious labour to nobles celebrating royal ceremonies. These were not mere records; they were living literature, recited, sung, and memorised by scholars who viewed these verses as the foundation of civilisation.

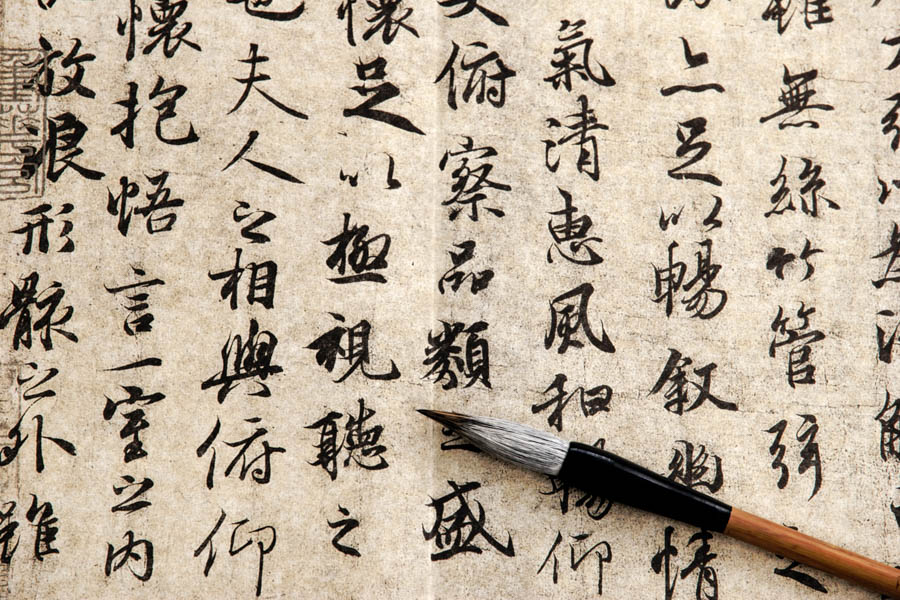

At Qufu's Confucius Temple in Shandong Province, you can walk where the sage himself taught, his philosophy echoing through its courtyards. Confucius didn’t merely influence Chinese literature – he redefined its very purpose. His Analects, dialogues with his disciples recorded in refined classical Chinese, shaped the belief that words possess moral weight, and that the highest calling of a gentleman-scholar is to study, reflect, and serve society through wisdom rather than force.

Tours with sinologists can decode the layers of meaning in these ancient texts, revealing not just language but entire worldviews. The Former Residence of Confucius and the adjacent Kong Family Mansion offer glimpses into how literary culture was lived and how generations of scholars devoted their lives to mastering texts studied by their ancestors centuries before.

Tang and Song Dynasties: The Golden Era of Chinese Poetry

Many consider the Tang Dynasty the pinnacle of Chinese literature – a remarkable period from 618 to 907 CE that reached artistic heights rarely equalled. The Tang produced masters whose verses still resonate – Li Bai, the romantic wanderer who wrote of friendship, wine, and moonlit mountains; Du Fu, whose technical brilliance and moral vision captured both personal suffering and collective conscience; and Wang Wei, whose landscape poems dissolved the boundary between observer and nature.

At Xi'an's Tang Paradise, a cultural park reconstructing Tang-era architecture and gardens, you can experience the aesthetic world these poets inhabited. Evening performances feature classical music and dance inspired by Tang court culture, while pavilions display plaques inscribed with famous verses. The experience helps modern audiences grasp how poetry was not separate from daily life but woven through it – shared at banquets, exchanged between friends, carved onto temple walls, and committed to memory by everyone from emperors to merchants.

The Song Dynasty (960-1279), following the Tang's collapse, developed ci poetry – lyrics written to match existing melodies, originally performed by professional singers. It was later elevated by scholars like Su Shi (Su Dongpo), fusing philosophical depth with emotional subtlety.

In Hangzhou, once the Song capital, sites associated with Su Shi reveal how the city's famous West Lake inspired generations of poets. Boat rides across the lake at dawn, when mist turns mountains into ink-wash landscapes, reveal why poets viewed nature not as backdrop but as a mirror of internal states – beauty and melancholy, permanence and change, all reflected in water and stone.

For those seeking deeper interaction, several institutions offer classical Chinese poetry workshops where calligraphers guide visitors by copying Tang poems in traditional script.

China’s Four Great Novels: A Journey Through Epic Storytelling

While poetry dominated classical Chinese literature, the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1912) dynasties marked what many consider the golden age of the novel. Four masterpieces stand out, each offering a distinctive perspective:

Romance of the Three Kingdoms transformed historical records of political intrigue and military campaigns into an epic tale about loyalty, strategy, and the meaning of heroism. Water Margin told the story of outlaw heroes who rebelled against corrupt officials – figures who remain popular in Chinese films and television. Journey to the West blended religious allegory with comic adventure that follows the Buddhist monk Xuanzang as he travels west with Sun Wukong, the Monkey King, and other supernatural friends. A Dream of the Red Chamber portrayed the decline of an aristocratic family while also looking at love, desire, fate, and the Buddhist idea that attachments to the world cause suffering.

At Beijing's National Library of China, exhibitions showcase rare editions of these novels alongside manuscripts and woodblock prints, offering insight into how stories circulated before modern publishing. The library's permanent collection includes Ming Dynasty editions, whose illustrations helped shape Chinese visual culture for centuries.

In Shanghai's literary quarter, around Duolun Road, bookshops specialising in classical literature offer modern editions and scholarly commentaries. Knowledgeable guides can arrange readings and discussion, helping Western readers navigate cultural references that might otherwise remain obscure – why certain flowers carry specific meanings, how family hierarchy shapes every interaction, and what religious concepts underlie seemingly simple plot points.

Journey to the West can also be followed through real locations. Xuanzang’s historical pilgrimage to India began in Chang’an (modern-day Xi’an), tracing a route through desert oases and Buddhist sites along the Silk Road, and sites along this route – the Mogao Grottoes at Dunhuang with their Buddhist murals and desert oases, where the monk rested – allow travellers to explore literature through geography, standing where history and legend converge.

Peking and Kunqu Opera: Bringing Chinese Literature to Life

Chinese literature has never been purely textual. For centuries, stories reached most people through performance – opera singers whose voices echoed across temple courtyards, storytellers in teahouses who could unfold a tale over weeks of sessions, and shadow puppeteers whose flickering silhouettes enacted legends of gods and heroes.

Peking Opera, which took shape during the Qing Dynasty, represents the pinnacle of this performative tradition. At Beijing's Liyuan Theatre or the Huguang Guild Hall, watching a performance shows how literature thrives beyond the page. The Four Great Classical Novels appear regularly in opera adaptations, their sprawling narratives condensed into two hours of music, movement, and symbolic spectacle.

UNESCO has recognised Kunqu Opera, an older and more refined form, as a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity. In Suzhou, where Kunqu originated, intimate performances in classical gardens – perhaps twenty or thirty spectators gathered around a small stage at dusk – offer a rare experience impossible to replicate elsewhere. Traditional melodies, poetic librettos, and decades of disciplined training create something at once ancient and immediate: literature living through performance, not just on the page.

For the curious traveller, opera experiences can be arranged that explain the symbolism of makeup, the years of training required to master a single role, and the links between costume colours, classical poetry, and centuries-old philosophical ideas.

Modern Chinese Literature: From Lu Xun to Liu Cixin

The May Fourth Movement of 1919 reshaped Chinese literature as profoundly as any political revolution. Writers such as Lu Xun rejected classical Chinese in favour of the vernacular, believing literature should awaken ordinary people. His short stories – The True Story of Ah Q and A Madman's Diary – used satire and psychological depth to expose social decay and question tradition during China’s struggle to modernise.

In Shanghai, the Former Residence of Lu Xun preserves the writer’s study, with manuscripts and personal effects still in place. Nearby, Duolun Road hosts small museums and literary cafés, where contemporary thinkers continue debates on tradition, modernity, and what it means to be Chinese in a globalised world.

Modern Chinese literature addresses issues that remain urgent: the trauma of war and revolution, tensions between individual and collective identity, the contrast between rural life and urban transformation, and the cost of rapid modernisation. Authors like Mo Yan, who won the Nobel Prize in Literature, blend folklore with realism, to create novels both timeless and sharply relevant. His book Red Sorghum is both mythic fable and unflinching historical reflection.

Chinese science fiction has also gained international recognition. Liu Cixin's The Three-Body Problem trilogy combines complex physics with philosophical inquiry into humanity's place in the cosmos, achieving global bestseller status and offering a uniquely Chinese vision of universal questions.

The digital revolution has transformed Chinese literature in unimaginable ways. Web novels –serialised fiction published chapter by chapter on platforms like Qidian and Jinjiang – have created an ecosystem where millions of readers follow stories in real time, leaving comments that influence how plots unfold. This participatory form blends popular entertainment with surprising literary sophistication, and some web novels achieving print publication and adaptation into television series watched by hundreds of millions.

For travellers interested in the digital novel phenomenon, visit conventions in Shanghai and Beijing, where authors meet fans, or spend time in literary cafés near universities, where readers debate the latest chapters on their phones – literature as vivid, social, and alive as it was in Tang dynasty teahouses, now shared through glowing screens.

Chinese Literary Tourism: From Beijing Libraries to Suzhou Gardens

For travellers seeking meaningful engagement with Chinese literary culture, opportunities abound across the country – each destination revealing a different facet of this vast tradition.

Beijing remains the literary heart of the country, with the National Library of China houses the world's largest collection of Chinese manuscripts and historical texts. The city's numerous theatres stage nightly opera performances, while literary sites like the Lu Xun Museum and the Lao She Teahouse honour modern masters and their enduring legacies.

Shanghai blends tradition and innovation. Duolun Road preserves the spirit of the 1920s–30s literary renaissance, while contemporary bookshops like Sinan Books offer elegant spaces for readings and discussions. The city hosts major literary events, including the Shanghai International Literary Festival and the Shanghai Book Fair. These events bring together Chinese and international writers to share ideas and celebrate storytelling.

Hangzhou and Suzhou – cities of gardens, water, and poetry – invite visitors to experience landscapes as literature. Walking through classical gardens like Suzhou's Humble Administrator's Garden or the Lingering Garden, poetry is etched into stones, pavilions are named after famous lines, and views are arranged as three-dimensional verses where rock, water, and plant combine into compositions as meticulous as any written text.

Xi’an, the ancient capital, connects visitors to Tang Dynasty poets and the historical journey of Xuanzang, whose pilgrimage inspired Journey to the West. The city's museums exhibit calligraphy and manuscripts from China's golden age of poetry, while evening performances of Tang music and dance revive the cultural world that inspired generations of verse.

For those drawn to contemporary literature, major cities host author readings, literary cafés, and book festivals throughout the year.

The Living Tradition of Chinese Literature: Past, Present, and Beyond

For the culturally curious traveller, Chinese literature offers a one-of-a-kind experience: a tradition that is both ancient and contemporary, rooted in history yet concerned with timeless human questions. Reading Tang poetry is like sharing the experience of watching moonlight on mountains with someone who has been dead for 1300 years.

When you watch Peking Opera, you see stories that have touched people for generations. Their meanings evolve, but their emotional force endures. Speaking with readers in Beijing or Shanghai reveals how modern novels still wrestle with identity, belonging, ethics, and the relationship between self and society.

The greatest literature transcends time and place. It speaks of love and loss, ambition and failure, the search for meaning, the solace of beauty, the strength of friendship, the burden of duty, and the yearning for freedom. Chinese literature has explored these themes in a way that is both deep and consistent, making a body of work that is worth reading for a lifetime.

For sophisticated travellers, exploring China’s literary heritage means more than museums and performances. It means standing in landscapes that inspired poets, understanding how physical beauty translates into verse. It means watching how contemporary Chinese readers engage with both classical works and modern novels and how literature shapes conversations about what China was, is, and might become. It means discovering that words written centuries ago in a language you may not speak can still move you, that the human voice echoing across time and space remains literature's greatest gift.