Martial arts are a vital part of Chinese culture, blending military traditions with philosophical thought and spiritual discipline. Over the course of thousands of years, they have influenced not only methods of combat but also a broader worldview - one in which physical strength is balanced by inner harmony and self-control.

Explore the origins of Chinese martial arts, uncover the principles that guide their practice, and learn how they continue to shape both Chinese identity and global culture in the modern world.

History of the Rich Heritage of Chinese Martial Arts

The earliest written references to martial arts in China date back to the Xia Dynasty (2070–1600 BC). When Huangdi’s army defeated the army led by Chi You in 2697 BC by using Jiao Di (角抵), a form of wrestling and grappling. Even at that time, hand-to-hand combat and weapons training were practised for hunting, military preparation, and self-defence. Over time, these physical disciplines were enriched by philosophical ideas, transforming them into a path of self-cultivation and spiritual growth.

Wrestling (dou) dates back to the Shang Dynasty (1600 BC–1046 BC), as inscriptions on oracle bones represent some of the earliest documented military practices, marking the foundational historical records of wrestling in China.

During the constant states of war between the Warring States period (475–221 BC) and the Zhou dynasty (1046–256 BC), martial training focused primarily on archery and horseback combat. After China’s unification under Qin Shi Huang (221–207 BC), a wrestling style known as Jiaoli gained popularity. This form of competitive grappling is considered a forerunner of formal martial arts tournaments and duels.

The Han Dynasty (202 BC–220 AD) saw martial arts evolve further with the spread of spear techniques and the emergence of the first “animal” styles, including monkey, tiger, snake, dragon, and mantis. This combination of techniques, such as wrestling, grappling, barehanded combat and weapons, later became foundational components of traditional wushu.

A pivotal moment in Chinese martial arts history was the arrival of Bodhidharma, whose origins remain uncertain; he is thought to have been either a Persian from Central Asia or a monk from South India. He settled at the Shaolin Monastery around 527 CE, where he founded the first Chan Buddhist school and taught the monks a set of physical exercises known as Yijin Jing Qigong. These practices became central to the development of both physical conditioning and spiritual discipline in Chinese martial arts.

During the Tang Dynasty (618–907), an imperial martial arts examination system was established. These multi-level exams were held regularly across the empire and, like their civil counterparts, served as a mechanism to select the most talented fighters and generals for state service.

Although the Mongol Yuan dynasty prohibited civilians from practising martial arts to consolidate its power, Kublai Khan established martial arts schools. There, a complex combination of physical skills, weapons mastery, and mental balance was taught to create a strong army.

Wushu experienced a revival under the Ming Dynasty (1368 to 1644). This period marked a resurgence in many cultural practices, including martial arts, as the Ming established a strong national identity after the Mongol Yuan Dynasty. Later, under the Qing Dynasty (1644 to 1912) and its Manchu rulers, martial arts techniques were once again restricted to members of the imperial army. However, many commoners continued to practise in secret, preserving ancient knowledge through underground traditions.

In modern times, following the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, Chinese martial arts gained international recognition. Starting in the 1980s, global tournaments began to be held regularly. Wushu will be granted the status of official sport in the Dakar 2026 Youth Olympic Games. This firmly establishes it as a modern global discipline rooted in centuries of tradition.

Choose Your Wushu Style

Chinese martial arts have evolved over thousands of years, showcasing the spirit of various eras and regions. Today, there are nearly 400 officially recognised styles in China alone, each with its own techniques, philosophy, and character. Discover which style resonates with you.

Bagua Zhang / Eight Trigram Palm (八卦掌) is a traditional Chinese martial art that emerged during the Qing dynasty (1644–1912). Founded by Master Dong Haichuan, it emphasises circular movements and fluid palm transitions. Students practise walking in circles and shifting palm positions to evade linear attacks, focusing on wrist control and silent footwork. Rooted in the cosmological theory of the Eight Trigrams, Bagua Zhang’s philosophy is expressed through palm shapes with movements resembling an intricate dance.

Training is offered in many regions of China, especially in the Wudang Mountains (武当山), known for its Taoist kung fu culture.

A notable school is the Wudang Mountain Kung Fu Academy (WDKF), which welcomes students of all levels for training ranging from one month to one year.

Website: https://www.wudangkungfu.net/

Drunken Boxing / Zui Quan (醉拳) is a distinctive style of Chinese martial arts that mimics the erratic movements of an inebriated person. Its power lies in deception: the practitioner appears to stumble, sway, or collapse, only to strike with sudden force and precision. Every movement is carefully controlled, masking advanced combat skills beneath a facade of unsteadiness. Acrobatics, misdirection, and fluid transitions are key elements of the style, demanding exceptional coordination, flexibility, and physical discipline.

One of the best places to witness the dynamic techniques of drunken boxing is the Kunyu Mountain Shaolin Martial Arts Academy in Shandong Province. This renowned centre of traditional kung fu regularly stages demonstrations and takes part in martial arts festivals dedicated to classical Chinese styles.

Website: https://www.chineseshaolins.com/

Eagle Claw / Ying Zhao (鷹爪派) origins date back to the Song Dynasty (960–1279), attributed to General Yue Fei, with significant developments occurring throughout the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1912) dynasties. It is a wushu style known for its intricate techniques and unpredictable combat sequences. It focuses on grabs, throws, and targeted strikes to pressure points, relying on sudden, sharp movements to catch opponents off guard. Training includes high jumps with leg lifts, mid-air body turns, and signature one-legged squats that resemble an eagle’s stance. The style takes its name from the distinctive hand position, with fingers bent and tensed to form a claw-like shape.

Grandmaster Guo Xian He, a descendant of the King of the Eagle, Great Grandmaster Chen Zi Zheng, continues to teach the Eagle Claw Style.

Website: https://yingshouquan.com/

Gongfu / Kung Fu / Wushu (武術) refers to several different styles of Chinese martial arts that include traditions such as Shaolin kung fu, Tai Chi, Wudangquan, and others. The term “kung fu” means “diligence” or “mastery through hard work” and traditionally applies to any skill requiring sustained effort. In the West, however, it has become synonymous with Chinese martial arts. Within China, the more accurate and widely used term remains wushu.

For those eager to study martial arts in depth, kung fu schools throughout China welcome beginners to join training programmes. The Shen Jiangfei Martial Arts School (Yunnan/Fujian) offers personalised training sessions.

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/jiangfeishen/

Hung Ga / Hongjiaquan (洪家拳) is one of the most widely practised styles of kung fu from southern China, from the 17th century. It emphasises a low, stable stance with deeply bent knees, combined with strong hand and foot strikes. The system draws inspiration from traditional “animal” styles, each embodying a distinct principle: the tiger’s strength and firmness, the crane’s balance and precision, the snake’s fluidity, the leopard’s speed and intensity, and the dragon’s inner power and perseverance. Breath control is central to the practice, helping regulate the flow of qi (气) and allowing practitioners to concentrate on even the subtlest movements.

Hung Ga is actively taught in martial arts schools across southern China, particularly in cities such as Hong Kong, Foshan, and Guangdong. Notable training centres include the Foshan Hong Sheng Martial Arts Academy, Huang Fei Hong Pugilism Hall, and the Foshan Jingwu Society, among others.

Ninjas, or shinobi (忍者), are primarily a Japanese cultural phenomenon, though some origins are linked to China. They emerged after the fall of the Tang dynasty, as military aristocrats migrated to Japan, sharing their ideas and martial arts proficiency. The art of the ninja matured during the Sengoku period (15th-16th centuries), functioning as scouts, saboteurs, and spies amidst civil unrest. To learn more about Japanese martial arts, visit our dedicated guide.

In Western culture, ninjas are often incorrectly represented as part of Chinese martial arts in films, leading to confusion among many individuals regarding their true origins.

Shaolin Kung Fu (少林功夫) is one of the oldest forms of Chinese martial arts, with roots in the Shaolin Monastery dating back to the 5th century. It developed as a system that integrates combat techniques, Buddhist philosophy, and the pursuit of harmony between body and mind. Training includes stances, strikes, acrobatics, weapons work, qigong breathing, and meditation. The practice emphasises endurance, discipline, and internal balance as essential foundations for true mastery.

The Shaolin Temple in Henan Province is recognised as the birthplace of Chinese martial arts, linked to Bodhidharma, and remains one of China's key Buddhist centres. Shaolin monks gained fame for their expertise in staff fighting and for developing their own system of unarmed combat. Today, the temple is both an active monastery and a major tourist destination, where visitors can watch martial arts demonstrations and explore nearby wushu academies. Year-round retreats offer intensive training programmes that combine physical practice with meditation.

Located near the monastery, the Shaolin Tagou Martial Arts School is a major wushu academy in China. It welcomes both Chinese and international students, offering a range of short-term and long-term courses.

Website: https://www.shaolintagou.org/

Taijiquan (太极拳), or Tai Chi Chuan, inscribed in 2020 on the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, is one of the most renowned Chinese martial arts, known for its slow, flowing movements and focus on harmony between body and mind. Rooted in Taoist cosmology, including principles of yin and yang, Confucian thoughts and traditional Chinese medicine, it emphasises the cultivation of internal qi energy. In addition to its martial applications, Tai Chi Chuan is widely practised by people of all ages for health benefits, improved coordination, breathing control, and inner balance.

At the heart of Tai Chi Chuan lies the idea of balancing opposites in continuous motion. It is often valued as a meditative practice that helps reduce stress and promote mental clarity. It can also enhance physical fitness, flexibility, and rehabilitation. Several distinct styles are practised today, but there are five major ones: Yang style, the most widespread, features smooth, continuous movements; Chen style blends slow motion with sudden bursts of force; Sun style includes quick, agile side steps; Wu style emphasises low stances and subtle weight shifts; and Wuhao style develops dense and compact movements.

Tai Chi Chuan can be studied at dedicated centres across China. In Beijing, for example, the Yang Family Tai Chi School offers group masterclasses. The Chenjiagou Taichi School in Henan is renowned for its Chen style Tai Chi Chuan.

Practising Tai Chi in public parks is a common morning routine in many cities, including Chengdu, Shanghai, and Beijing, where both locals and visitors are welcome to observe or join group sessions.

Website of Yang Family school: https://yangfamilytaichi.com/china-tai-chi/

Website of Chenjiagou Taichi school: https://www.chenschool.com/

Wing Chun (咏春拳) is a distinctive style of Chinese martial arts that developed primarily in the southern province of Guangdong, especially in Foshan and Hong Kong. It rose to global prominence in the 20th century through the teachings of Master Yip Man (or Ip Man), who famously trained Bruce Lee. The style became widely recognised for its speed, precision, and cinematic appeal, thanks in part to its portrayal in martial arts films.

Wing Chun emphasises close-range combat, direct strikes, and rapid reflexes. Core elements of training include hand sensitivity drills, coordination, speed development, and practice on the Muk Yan Jong, a wooden dummy used to refine targeting and technique. The system focuses on efficient movement and the ability to control the opponent’s attack line.

Today, numerous Wing Chun schools and clubs operate throughout southeastern China, many led by students and successors of Yip Man who continue to teach according to his methods and uphold the tradition of the style.

A traditional school worth considering is the Qufu Shaolin Kung Fu School, where instruction is provided by Master Zhang Wei.

Website: https://www.shaolinskungfu.com/

Xing Yi Quan (形意拳), or Form-Intent Fist, is one of the oldest styles of Chinese martial arts. It is built on the integration of external technique with internal focus. The system is based on the theory of the five elements, expressed through five core strikes, and the “twelve animals”, whose movements imitate animal behaviour. The style is known for its direct attacks, explosive power, and compact, efficient movement.

While General Yue Fei, a legendary figure from the Song Dynasty (960–1279 AD), is often credited with the creation of Xing Yi Quan, this claim is debated among historians. Xing Yi Quan took shape at the end of the Ming dynasty and evolved further during the Qing dynasty. The earliest documented master of the style is Ji Longfeng. In the 19th century, Xing Yi Quan spread widely across northern China, particularly in Shanxi and Hebei. Training typically includes the Santishi stance, fundamental strikes, progressive form work, and breathing and concentration exercises.

Nowadays, Xing Yi Quan is practised in martial arts schools across China, especially in Beijing and Shanghai. The Yin Cheng Gong Fa Association (YCGFA) in Beijing aims to help you learn or develop your skills.

Website: https://www.ycgf.org/ycgf_home.html

Explore the Artistry of Chinese Martial Arts Weapons

Weapons hold a special place in the kung fu tradition, seen as an extension of the practitioner's physical and mental training. Each weapon carries its own philosophy and symbolic meaning, contributing to the development of strength, coordination, and tactical awareness. Below is a selection of key weapons that have shaped Chinese martial arts over the centuries.

- Gun / Staff (棍) – One of the oldest and most versatile Chinese weapons, the staff appears in both long and short forms, crafted from wood or modern materials. Training with the staff builds strength, stamina, and spatial awareness.

- Dao / Broadsword (刀) – A single-edged weapon with a slight curve, the broadsword features a handle curved in the opposite direction of the blade for balance and control. Its design allows for powerful slashing and thrusting techniques.

- Jian / Straight Sword (劍) – A double-edged weapon with a refined, symmetrical design, the straight sword was favoured by scholars and nobility. The blade is often diamond-shaped, and the handle may be short for single-handed use or long for two-handed techniques.

- Qiang / Spear (槍) – Known as the “king of weapons”, the spear combines reach, precision, and agility. A sharp blade is mounted on a long shaft, traditionally up to 5 metres in length, though shorter versions are more commonly used.

In addition to these “four great weapons”, Chinese martial arts also employ a wide array of specialised tools:

- Sanjiegun / Three-section staff (三节棍) – A flexible weapon made of three wooden or metal segments connected by chains, valued for its unpredictability and speed.

- Guan Dao / Polearm (偃月刀) – A heavy weapon with a broad, curved blade mounted on a long pole, used for sweeping and chopping attacks.

- Hu Tou Gou / Shuang Gou / Hook Swords (钩) – A matched pair of weapons with curved blades and hooked tips, designed for trapping and disarming opponents.

- Chan Zhang / Monk’s Spade (月牙鏟) – A double-ended pole weapon with a crescent blade on one side and a flat spade on the other, traditionally carried by travelling monks.

- Bian / Hard Whip (鞭) – A rigid weapon composed of metal segments or links, requiring precise control for effective strikes.

- Liu Xing Chui / Meteor Hammer (流星錘) – A heavy weight attached to a long rope or chain, used for high-speed, long-range attacks.

- Sheng Biao / Rope Dart (绳镖) – A pointed metal dart fixed to a long rope, allowing for fast, deceptive strikes and complex retrieval manoeuvres.

These weapons are not only tools for combat but also expressions of the depth and diversity of Chinese martial arts philosophy. Each requires years of dedicated practice to master, reflecting the discipline and artistry at the heart of wushu.

Who Are the Most Influential Chinese Martial Arts Masters?

Chinese martial arts have evolved over centuries, thanks to the contributions of exceptional masters who preserved and advanced these traditions. Below are some of the most influential figures who left a lasting legacy in martial arts history and popular culture:

- Zhang Sanfeng (12th century) – A legendary figure credited with creating Tai Chi. Often regarded as a spiritual teacher, he is associated with Confucian and Taoist philosophy.

- Chen Wangting (1580–1660) – Founder of Chen-style Tai Chi, he played a key role in shaping the development of the Taijiquan tradition.

- Wong Fei-hung (1847–1925) – A historical martial artist, physician, and folk hero associated with Hung Ga. He became a symbol of honour and mastery in southern Chinese kung fu.

- Guo Yunshen (1829–1898) – Celebrated for his powerful strikes and technical precision, Guo was a master of several internal styles, particularly Xing Yi Quan.

- Huo Yuanjia (1868–1910) – A national hero and founder of the Chin Woo Athletic Association, Huo promoted principles of fair combat and national pride.

- Li Shuwen (1864–1934) – A master of Bajiquan, he earned a reputation for his fearsome close-range combat skills and was revered as a fist-fighting virtuoso.

- Ip Man (1893–1972) – A renowned Wing Chun master, known for formalising and widely teaching the style. He is also remembered as Bruce Lee's mentor.

- Cheng Man-ch'ing (1902–1975) – Instrumental in bringing Tai Chi to the West, he adapted traditional methods to modern contexts and introduced Chinese martial arts to a global audience.

- Bruce Lee (1940–1973) – A student of Ip Man and a pioneering figure in modern cinema, Bruce Lee had a transformative impact on global martial arts culture. He developed his own combat philosophy known as Jeet Kune Do.

Furthering Your Journey in Martial Arts

Embarking on a journey to discover Chinese martial arts extends far beyond mere practice in dedicated schools; it invites you to immerse yourself in its rich history and vibrant culture through a variety of engaging experiences. For those keen to delve into this multifaceted world, there are countless opportunities available to deepen your understanding and appreciation.

Online Learning Opportunities

Consider enrolling in online courses and webinars that focus on Shaolin Kung Fu, Tai Chi and Qigong. Many schools, such as the Traditional Shaolin & Tai Chi Martial Arts Academy in China, offer virtual programmes and Zoom classes that cover both technical instruction and the philosophical and historical foundations of martial arts. Lectures by masters and scholars provide insights into the evolution of styles and their cultural significance. Seminars and masterclasses often explore deeper philosophical dimensions rarely addressed in regular training sessions.

Website: https://www.kungfuschoolchina.com/masters

Join a local community

Finding a local martial arts club or community can greatly enrich your learning experience. Engaging with fellow practitioners provides camaraderie and shared insights while offering practical training opportunities. Look for local meet-ups, workshops, or community events to practise and discuss various martial arts.

Read widely

Reading specialised magazines and martial arts journals offers updates on contemporary developments and expert commentary. Books on Chinese philosophy, history, and aesthetics provide essential context for understanding the spiritual roots of martial arts. The posthumous book "The Tao of Jeet Kune Do" by Bruce Lee provides vital insights into his views on martial arts philosophy, enhancing your understanding of his discipline's deeper meanings.

Explore cultural landmarks and museums

Visiting significant cultural landmarks and museums can provide further context for your martial arts journey. The Wudang Mountains (武当山), a UNESCO World Heritage Site, are renowned for their rich Taoist kung fu culture. Other notable places include the fascinating Chinese Martial Arts Museums, located at 399 Changhai Road, Yangpu district, in Shanghai, and the Yip Man Memorial Museum in Foshan, each offering insights into the evolution and significance of various martial arts styles.

UNESCO: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/705/

Attend festivals, shows, and events

Plan to participate in the next International Shaolin Wushu Festival, held biennially in Zhengzhou, the capital of Henan, China. The 13th edition occurred in October 2024. It features competitions, workshops, and live demonstrations of various martial arts styles, offering a rich cultural experience. While the Shanghai World Grand Wushu Festival held annually typically attracts martial artists and enthusiasts from around the globe.

Eagle Claw performances can be seen at the Xiongan Xiangzhou Culture and Art Festival (雄安雄州文化艺术节), held in the Xiong'an New Area of Hebei Province.

These festivals showcase the beauty and diversity of martial traditions in a broader cultural setting, often blending martial

For a vibrant display of kung fu in a theatrical setting, visit the legendary Beijing Kung Fu Show at the Red Theatre, where acrobats, dancers, and gymnasts perform choreographed routines that showcase martial arts precision. Some tours to Beijing's Pearl Market include dinner followed by a costume show featuring kung fu demonstrations.

Website of The Red Theatre: https://redtheatrekungfushow.com/

Explore martial arts cinema

Martial arts cinema provides a unique lens through which to view the cultural context of these practices. One of the most iconic figures in martial arts film is Bruce Lee, whose most famous film, "Enter the Dragon", released in 1973, showcases his exceptional martial arts prowess and philosophical insights. While Chinese actor Jackie Chan's famous film “Drunken Master”, released in 1978, has significantly contributed to spreading knowledge of drunken boxing worldwide.

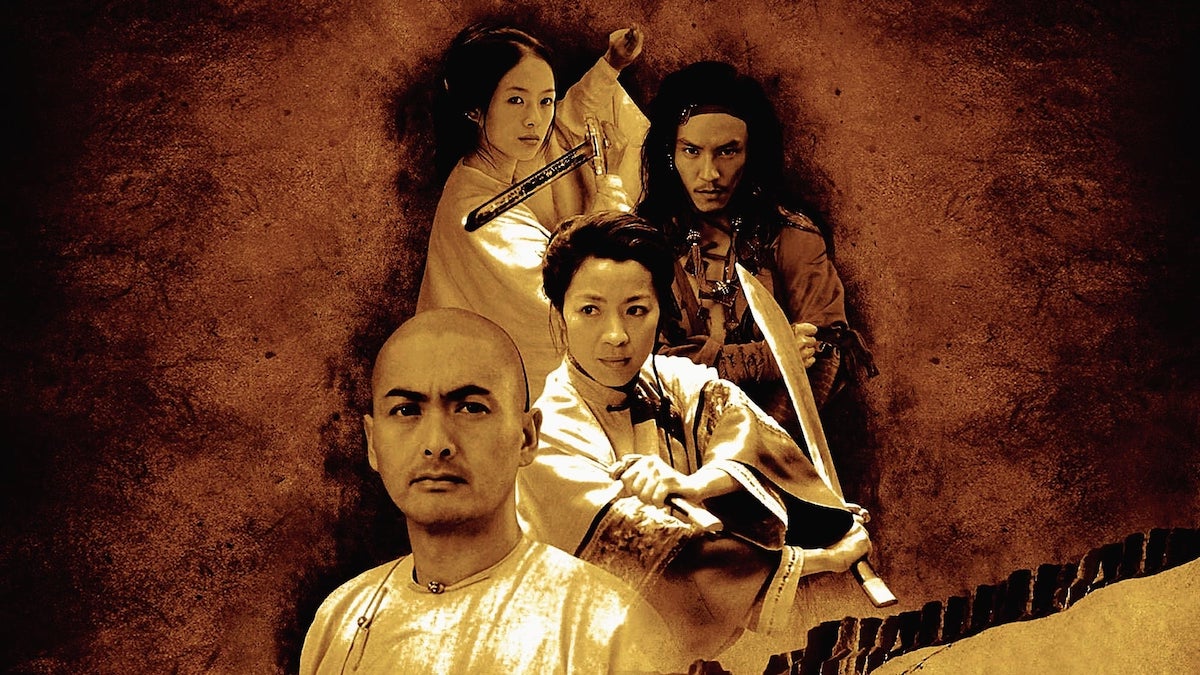

Watch also "Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon", by Ang Lee, released in 2000, a film that elegantly depicts martial arts while reflecting China's historical and cultural context.

Cultivate both body and mind

Martial arts develop not only physical ability but also character, focus, and emotional balance. Keeping a training journal can help you reflect on progress and challenges, while meditation and mindfulness exercises enhance mental clarity. This integrated approach transforms martial arts into a path of personal growth. Practising Tai Chi Chuan in a garden in China in the morning is a serene and enriching experience and provides genuine cultural integration.

Chinese martial arts continue to evolve, inspiring practitioners across the globe. Engaging with these traditions opens the door to deeper cultural understanding and reveals martial arts not only as a system of self-defence but also as a way to explore the self and live in greater harmony with the world.