Sculpture and stone carving in China embody the spiritual aspirations and artistic ideals of the Chinese people through the ages. Monumental Buddha statues, temple reliefs, and graceful figurative works found in burial complexes and garden ensembles reflect symbols of faith, philosophy, and history. Their balanced proportions and finely carved details give each piece a distinct character, turning it into both a reflection of its time and a guardian of cultural memory.

Discover this art in all its richness - trace the legacy of dynasties, explore artistic techniques and imagery, and see how stone sculpture and carving shaped the aesthetics of temples, tombs, and cities. By studying these stone creations up close, you can sense the breath of antiquity and understand the conceptions and values that have defined China’s artistic tradition for centuries.

Historical Development of Chinese Stone Sculpture and Carving

Stone carving in China has a history spanning over 5,000 years, evolving from rudimentary Neolithic tools to refined artistic achievements that reflect the country’s spiritual and cultural identity.

The earliest evidence of stone carving dates to the Neolithic period, particularly in regions such as Lingnan, where early communities shaped tools and decorative items from available stone. These primitive carvings often bore simple geometric patterns and laid the technical and symbolic foundation for later developments.

By the time of the Bronze Age in East Asia (circa 3100–300 BCE), carving methods had advanced notably. While metalwork dominated the era, the aesthetic values of that time also began to influence stone architecture and ornamentation.

A significant leap in monumental sculpture occurred during the Qin (221–206 BCE) and early Han (202 BCE–220 CE) dynasties. Tomb artefacts from the Western Han period – such as those found at the Mausoleum of the Nanyue King in Guangzhou – show increasingly complex decorative carvings. The first known examples of free-standing stone statues in Chinese history date from this time, most notably the sculptural ensemble near the tomb of General Huo Qubing (140–117 BCE), whose massive animal and mythical beast carvings remain unmatched in scale and variety.

During the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE), Chinese stone sculpture reached new heights. Cave temples became important centres for artistic expression, combining Buddhist devotional imagery with native aesthetics. In Sichuan Province, the colossal 71-metre Leshan Giant Buddha was carved directly into a cliffside, while the Yungang Grottoes in present-day Shanxi – initiated earlier in the Northern Wei dynasty – flourished with thousands of meticulously carved bodhisattvas. These works exemplify the Tang era's distinct blend of grandeur and grace.

The Song dynasty (960–1279) saw a shift from monumental sculpture to more intimate, intricately carved reliefs, often integrated into religious or architectural contexts. A resurgence of large-scale stone art came during the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1912) dynasties. This period introduced a more ethnically diverse aesthetic, incorporating elements from Tibetan, Mongol, and other regional traditions into Han Chinese artistic forms. Bas-reliefs in palaces and temples were frequently used to express themes of imperial legitimacy and religious harmony.

In the 20th century, the role of sculpture evolved again, reflecting the political and ideological changes of modern China. Public memorials and monumental stone ensembles, such as those found around Tiananmen Square or at the Summer Palace in Beijing, embody a narrative of national identity, while contemporary sculptors continue to explore new materials and conceptual approaches.

Today, traditional hand-carving techniques are preserved in places like Dangcheng Town in Hebei Province, a centre for marble craftsmanship. Workshops such as Trevi Art and Culture produce both classical and modern sculptures for domestic and international collectors, demonstrating the enduring vitality of stone carving in Chinese artistic life.

Types of Stone Sculptures in China

Stone sculpture in China takes many forms and fulfils diverse functions. It is closely tied to religious ritual, serves as an architectural ornament, and exists as an independent art form. For centuries, stone and jade works have united practical, spiritual, and aesthetic purposes - from Buddha statues and dragon carvings to bas-reliefs with floral motifs.

Monumental Religious and Mythological Sculptures

A large part of China’s sculptural heritage consists of Buddhist figures found in temple complexes and cave sanctuaries. Among the most renowned are the monumental rock-carved Buddhas of Longmen and Dunhuang. These immense statues and reliefs impress with their grandeur and variety of forms, while the serene faces of the bodhisattvas reveal exceptional grace and refinement of detail.

Alongside Buddhist imagery are stone carvings inspired by Taoist and Confucian philosophy. About 70 kilometres from Xi’an lies Louguantai Temple, a Taoist sanctuary where, according to legend, Laozi composed the Tao Te Ching, the foundational text of Taoism. Here stand striking sculptural compositions portraying the sage and his disciples, along with mythological figures such as immortals and dragons, which symbolise power and transformation. In Beijing, the Temple of Confucius houses massive stone stelae engraved with the Thirteen Classics - the core scriptures of the Confucian canon.

Sculpture as an Element of Architecture

For centuries, stone has been used to adorn temples, pagodas, and palace complexes. Decorative compositions on walls, columns, and entrance gateways carried particular symbolic weight, combining ornamental motifs with depictions of mythological creatures. These embellishments not only enhanced architectural expressiveness but also held sacred significance and protective power. One of the most recognisable examples is the pair of stone lions guarding temple and palace entrances, symbols of strength and divine guardianship. Traditionally, they appear in pairs, representing the masculine and feminine principles - the dual forces of the universe.

Sculptural reliefs also enrich interiors. Elegant floral bas-reliefs, for instance, embellish the Great Mosque of Xi’an. Walls, fences, gates, and monumental arches known as paifang (牌楼) are often adorned with delicate carvings of trees, flowers, and shrubs, lending them both beauty and symbolic depth.

Commemorative and Historical Chinese Stone Sculpture

In preserving the legacy of notable figures and events within Chinese history, commemorative and historical sculptures play an essential role. Statues of distinguished military leaders and nobles frequently decorated imperial mausoleums, celebrating the achievements and might of great rulers while preserving their legacy in stone. The Qianling Tomb (乾陵), built in honour of Emperor Gaozong and his wife Wu Zetian, China’s only female emperor, is especially striking. Across its vast grounds stand over a hundred statues, including representations of foreign envoys paying homage to the powerful Tang rulers.

Additionally, numerous dynastic monuments showcase the grandeur of emperors and their contributions to the state. These sculptures serve not only to honour the past but also to instil a sense of pride and identity within local communities. Whether in public squares or within tomb complexes, these stone sculptures narrate the rich stories of China’s historical tapestry.

Animal sculptures were also commonly placed beside tombs, as in the Maoling Tomb of Emperor Wu of the Han dynasty. The most celebrated tomb in this complex is that of General Huo Qubing, surrounded by massive, roughly hewn stone figures of a horse, elephant, bull, and camel - symbols of the commander’s strength and valour.

Civic and Public Sculptures in China

A wide range of artworks that enhance the cultural landscape of communities can be found all over China. Statues in public spaces often commemorate important historical events or figures that resonate with local identity. Many cities boast sculptures honouring freedom fighters or significant milestones in their history, which serve both educational and inspirational purposes for residents and visitors alike.

Within this category, ornamental sculptures are positioned on civic buildings, fountains, and parks, featuring intricate designs that add aesthetic value. Some may depict mythological creatures or symbolic motifs that convey deeper cultural meanings.

Moreover, functional sculptures, such as those integrated into fountains or garden designs, serve practical purposes while displaying artistry. These works can transform spaces, making them not only visually appealing but also inviting places for community gathering. By blending beauty with functionality, these sculptures enrich the civic environment and strengthen the cultural identity of the area.

Materials Used to Sculpt and Carve Stones in China

Throughout history, Chinese sculptors worked with a variety of materials, stone being the most widely used material in monumental sculpture. Various types of stone, including marble, limestone, and granite, have been employed for different sculptural purposes.

Marble was prized for its smooth texture and suitability for intricate carving; it offers exceptional detail.

Limestone is known for its malleability and ease of shaping; limestone has been a versatile choice for many sculptors.

Granite is valued for its durability; it was often used for large, robust sculptures.

Soapstone is a soft metamorphic rock with a high talc content, typically scoring 1 to 3 on the Mohs scale, though some denser varieties may reach up to 5. Its smooth texture and ease of carving made it a popular material for both decorative sculpture and practical objects such as dishes, teapots, and stoves. Found in a broad palette of colours – white, grey, black, green, pink, purple, red, and brown – soapstone continues to be valued for its versatility and natural beauty.

Jade, though less common in large works, was especially valued for smaller sculptures. It was used to create funerary figurines, amulets, and ornaments, admired for its translucency and the way it caught the light.

The choice of material often depended on geography, but there can be regional variations in what materials were accessible. In northern China, sculptors typically worked with limestone and sandstone, widely available in the Shanxi and Henan regions.

Qingtian stone carving originates from Qingtian County in Zhejiang Province, on China's eastern coast. The region is renowned for its unique variety of soapstone, prized for its fine grain, vivid colours, and softness, which allow for remarkable refinement and intricate artistry in carving.

Southern provinces, on the other hand, had access to marble and granite, allowing for works with crisper contours and refined polishing. Soapstone is primarily sourced from regions like Fujian Province and some areas in Jiangxi Province.

Moreover, jade was mainly sourced from Xinjiang and transporting it to the empire’s central regions increased its cost and prestige.

In addition to native materials, precious stones arrived in China via the Silk Road and maritime trade routes. Records from the Qing dynasty’s imperial workshops document regular shipments of costly raw materials and semi-finished stones for artistic use.

Over time, craftsmen across China mastered a wide range of materials, elevating stone carving to exceptional technical and aesthetic standards.

Chinese Stone Sculptures and Carving Technique

Chinese sculptors paid meticulous attention to preparing their materials. Stones were carefully selected for colour, texture, and structural integrity. Large blocks were roughly shaped at the quarry to ease transportation, with finer work completed at the installation site.

Traditional Carving Methods

The sculpting process began with coarse shaping: craftsmen used chisels and hammers to remove excess material and define the basic form. This was followed by more detailed carving using chisels and gouges to create facial features, folds of clothing, and decorative elements. The final stage was polishing, done with sand or quartz powder, which enhanced the sculpture’s lustre and emphasised subtle details in drapery and expression.

Among the most renowned traditional techniques are Qiaose (俏色) – which uses the natural colour variations of the stone to accentuate particular features – and Han Badao (汉八刀), or “eight Han strokes”, a minimalist method that achieves form through a few decisive chisel cuts.

Tools

To shape stone, artisans used an array of tools, including chisels, mallets, and rotary hand tools. These were employed to outline forms and define major features. Finer details were added with cutting tools and hand drills, allowing sculptors to render facial expressions and ornamental motifs with precision. For the most delicate work, miniature chisels and later rotary devices offered increased control and accuracy.

Modern Innovations

Since the 20th century, artists have adopted mechanical and electronic tools such as rotary-powered machines, flexible shaft devices, and circular saws. Today, sculptors also employ laser systems, ultrasonic cutters, and digital modelling, enabling greater accuracy and more complex forms. Synthetic abrasives are now widely used to achieve smooth finishes and intricate surface effects.

Contemporary Chinese Sculptors and Carvers

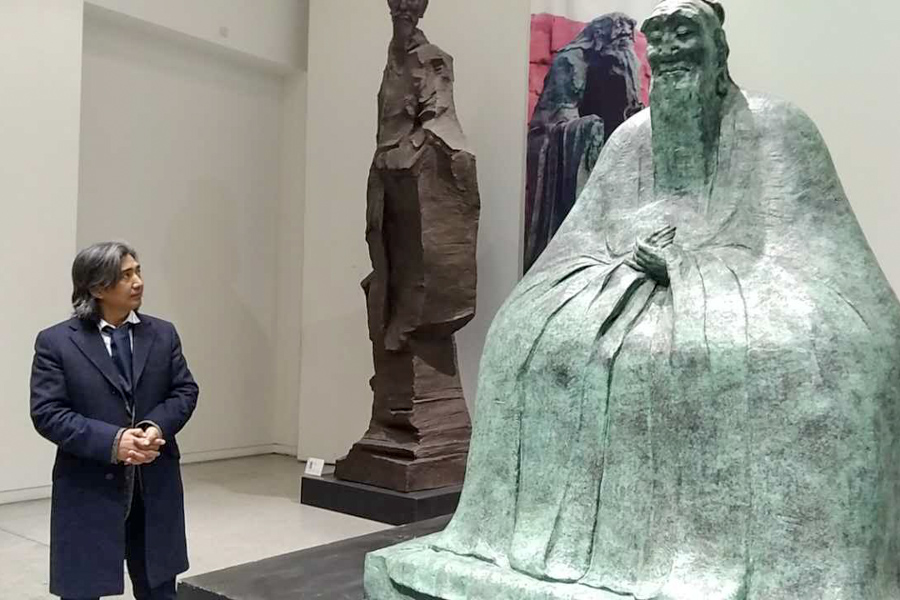

Photo by: www.srca-info.com

Chinese sculpture is undergoing a revival, driven by artists who skilfully combine traditional aesthetics with bold, contemporary ideas. Their works reflect the legacy of local artistic schools while expressing deeply personal visions, making each creation distinctive.

Wu Weishan is a leading figure in contemporary Chinese sculpture. An internationally recognised artist, his works are displayed in major institutions around the world. He is especially known for his portrayals of historical and cultural icons, including Confucius, Laozi, Leonardo da Vinci, Karl Marx, and Mao Zedong. His collection includes over 600 sculptures of notable individuals, as well as pieces commemorating key historical events. Highlights of his work can be seen at the National Art Museum of China (中国美术馆) in Beijing and at the Nanjing Museum (南京博物院), which houses a dedicated Wu Weishan Sculpture Hall.

Another major voice in Chinese sculpture is Sui Jianguo, widely known for his Mao Jacket series – bronze shells of the iconic garment that explore themes of history, authority, and personal freedom. He is also acclaimed for his series of monumental dinosaur forms constructed from wire mesh, offering a powerful metaphor for China’s rapid transformation and the tension between tradition and globalisation. Sui Jianguo’s work is exhibited in top Chinese institutions such as the Today Art Museum (今日美术馆) in Beijing, as well as leading galleries across Europe and the United States.

Zhan Wang is equally influential, renowned for his Artificial Rocks series. These sculptures recreate traditional Jiashanshi (假山石) garden stones using polished stainless steel. Their reflective, futuristic surfaces contrast with the natural forms they mimic, symbolising harmony and classical beauty within the modern urban landscape. Through these striking works, Zhan Wang brings elements of traditional residential design into a contemporary context.

Master artisans under Li Chengzhe dedicated three years to producing a remarkable work of art – a 20-metre-long, 1-metre-high interpretation of the iconic Along the River During the Qingming Festival, rendered through the Colour Stone Inlay Technique. This intricate composition blends stone carving, embossing, and woodwork, showcasing the depth of traditional Chinese craftsmanship. The Colour Stone Inlay tradition, which dates back around a century, has been officially recognised as part of China’s national intangible cultural heritage. While stone holds deep historical significance in Chinese sculpture, today’s artists often embrace a wider range of materials and mixed techniques. This shift reflects a living, evolving art form – rooted in heritage yet responsive to contemporary expression.

Cultural Significance of Chinese Stone Sculpture and Carving

In China, stone sculpture has always been more than decoration – it has served as a vessel for philosophical thought and a mirror of collective consciousness. Through reliefs and statues, artists have conveyed the values, beliefs, and ideals that have shaped Chinese society for centuries. Monuments in public squares continue to serve as focal points during national festivals, while stelae inscribed with the names of national heroes preserve intergenerational memory on days of historical significance. As it evolves over time, Chinese sculpture remains a medium of shared remembrance and a visual language accessible to all.

Sculpture also holds an important place in Chinese religious traditions. In popular belief systems, stone figures are often part of ceremonies tied to seasonal festivals and family rites. Guardian sculptures placed at gates or atop rooftops are thought to maintain balance between the human and spiritual realms.

The influence of stone sculpture extends beyond its own medium. Chinese painting, for instance, draws on sculptural composition, seeking harmony in volume and silhouette. Temple and palace architecture is closely integrated with carved ornamentation and monumental art, reflecting a deep reverence for history and folklore. Even in contemporary urban design, traditional sculptural motifs continue to appear – bridging past and present and ensuring the continuity of artistic heritage.

Must-Visit Stone Sculpture Masterpieces in China

China offers an extraordinary range of destinations for sculpture enthusiasts. Ancient stone figures, monumental Buddhist grottoes, and richly ornamented palace complexes reveal the depth and diversity of Chinese sculptural art. Below is a selection of some of the most remarkable sites in the country – impressive both in scale and in detail.

In Sichuan Province, the Leshan Giant Buddha (乐山大佛) stands 71 metres tall (233 feet), carved out of a red sandstone cliffside at the confluence of three rivers.

Further north, the Longmen Grottoes (龙门石窟) present a striking contrast: carved into limestone rock, this vast complex includes more than two thousand niches filled with tens of thousands of statues and bas-reliefs of Buddhas and bodhisattvas.

Among the notable achievements in Chinese stone carving are the Dazu Rock Carvings (大足石刻), in Chongqing, a UNESCO World Heritage site renowned for its impressive collection of over 50,000 statues, created between the 9th and 13th centuries. They form a unique ensemble that goes beyond religious themes. Here, scenes from daily life are depicted with remarkable detail, blending moral teachings with artistic expression.

On the western edge of China, near the city of Dunhuang, lie the Mogao Caves (莫高窟), or “Caves of a Thousand Buddhas”. For centuries, pilgrims and artists travelled to this sacred site, leaving behind exquisite murals and sculptures that make it a landmark of Silk Road heritage.

Other stone masterpieces include the impressive sculpture of Emperors Yan and Huang, carved in red stone from the Taihang Mountain by the Yellow River, standing at an overall height of 106 metrea (347.7 feet). Additionally, the 6-metre (20-foot) Mother River statue on the Yellow River in Lanzhou, Gansu, sculpted in granite,

The Eight Immortals statue is located in the Penglai Pavilion in Shandong Province. The Mazu goddess statue, worshipped by sailors for centuries, is found on Meizhou Island in Fujian and is made of granite.

Finally, the Zheng Chenggong statue in Xiamen, Fujian, which stands 15.7 metres (51.54 feet) tall and is carved from white granite. Those marvels leave visitors with lasting memories of their private tour in China.

Preservation and Conservation of Chinese Stone Sculpture and Carving

Chinese stone monuments face a wide range of environmental threats. Moisture, temperature fluctuations, and acid rain erode relief surfaces and damage sculptural details. Cave temples and monastery complexes are particularly vulnerable, as poor ventilation leads to moisture buildup, mould, salt crystallisation, and the loss of painted surfaces. Today, thanks to advances in technology and collaboration across disciplines, the deterioration of these sites can be significantly slowed.

Restoration and Conservation Techniques

Conservation efforts combine traditional methods with modern technology. At the Dazu Rock Carvings site, where water infiltration has caused damage, specialists used ground-penetrating radar and electromagnetic wave CT scanning to conduct detailed geological surveys. The curtain grouting method was introduced to detect underground fractures and create drainage channels. Additionally, microbial mineralisation – a technique at the intersection of microbiology, chemistry, and geotechnical engineering – is now being applied. At the Longmen Grottoes, 3D printing is used to reconstruct lost sculptural elements with impressive precision.

In several provinces, Chinese researchers are using artificial intelligence to monitor site conditions. At the Mogao Caves, for example, data is collected from over 100 fixed observation points, allowing annual comparisons to detect changes over time.

Heritage in Fragments: Digital Reconstruction

Digital reconstruction is also playing a key role in preserving heritage. One notable initiative is the Tianlongshan Caves Project (天龙山石窟项目), which focuses on a Buddhist cave complex in Shanxi Province. Many sculptures from this site were removed or fragmented over the centuries, with parts ending up in collections abroad. The project gathers data on these dispersed fragments to virtually reassemble the original works, offering a digital restoration of this unique monument in Chinese Buddhist history.

Discover the Chinese Art of Stone Sculpture and Carving

A deeper understanding of Chinese sculpture comes from learning about its historical and symbolic foundations. Recommended reading includes The Arts of China by Michael Sullivan, as well as publications by jade expert Angus Forsyth, such as Jades from China and Ships of the Silk Road: The Bactrian Camel in Chinese Jade. These works place sculptural traditions within a broader cultural context.

Leading museums in China also offer online collections and educational resources:

- National Museum of China (中国国家博物馆), Beijing

- National Art Museum of China (NAMOC) (中国美术馆), Beijing

- China National Arts and Crafts Museum (CTCM) (中国工艺美术馆), Beijing

- The Palace Museum (故宫博物院), Beijing Shanghai Museum (上海博物馆)

- Shaanxi History Museum (陕西历史博物馆), Xi’an

Travel Tips for Exploring Chinese Stone Sculpture

- Choose the right season. Spring and autumn offer the most comfortable conditions for visiting outdoor sites and cave complexes.

- Plan sufficient time. Large sites like the Longmen or Mogao Caves require at least half a day.

- Use an audio guide or hire a professional. Understanding Buddhist iconography and historical context can significantly enhance your visit.

- Focus on details. Beyond the grandeur, notice subtle elements like hand gestures, garment ornamentation, and facial expressions.

- Familiarise yourself with Chinese symbolism. Decipher the meanings behind common symbols and the significance of colours to deepen your appreciation of the sculptures and their cultural significance.

- Respect the heritage. Do not touch the sculptures and avoid using flash photography to help preserve these monuments for future generations.

Chinese stone sculpture remains a vital part of the country’s cultural heritage, embodying centuries of philosophy, belief, and artistic achievement. With increased efforts in conservation, museum curation, and digital innovation, the future of this art form continues to unfold – bridging the past with the tools of the present.