In the minds of people around the world, Uzbekistan's culture is a reflection of the Silk Road – vibrant textiles, majestic medieval architecture, warm hospitality, and delicious pilaf at lively celebrations.

But beyond these hallmarks of Uzbek culture, most of which are included in the UNESCO cultural heritage list, the country holds a wealth of lesser-known treasures: ancient petroglyphs, the ruins of Zoroastrian temples, and Buddhist monuments.

Material Culture of Uzbekistan

Architecture of Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan is renowned for its remarkable ancient and medieval architecture. The oldest surviving structures, now visible as ruins, are more than 2,000 years old – among them the fortresses of Ancient Khorezm, such as Toprak-kala and Ayaz-kala.

The country’s most significant architectural heritage, however, is found in the monuments of the Silk Road – the historic caravan route that connected East and West for centuries. One of its most iconic landmarks is the ensemble of three majestic madrasahs on Registan Square in Samarkand, a site that frequently ranks among the top attractions in Uzbekistan.

Other remarkable Silk Road-era structures stand in the ancient cities of Bukhara and Khiva. In Bukhara, the famed Kalyan Minaret and Miri-Arab Madrasah form part of the Po-i-Kalyan Ensemble, while Khiva is known for its striking inner city, Ichan-Kala. These cities have also preserved caravanserais, covered markets, and domed trading halls – vivid reminders of the region’s dynamic trading history.

Many of these architectural masterpieces are now UNESCO World Heritage Sites. They enchant visitors with their storybook beauty – towering minarets and monumental portals, intricate ornamentation, dazzling mosaics, and the shimmering azure domes that have become symbols of Uzbekistan’s architectural splendor.

Uzbekistan Cuisine

Uzbek cuisine is among the most distinctive in Central Asia. While it shares similarities with the culinary traditions of neighboring countries, it stands out for its unique flavors and character. Visitors from around the world, as well as regional neighbors from Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan, travel to Uzbekistan to experience its traditional dishes.

The centerpiece of Uzbek cuisine is pilaf, prepared in many regional variations. The most celebrated types include Samarkand, Tashkent, Bukhara, and Fergana-style pilaf. The culture of pilaf preparation in Uzbekistan, along with the rituals associated with it, vividly reflects the country's identity and has been recognized by UNESCO as part of the world's intangible cultural heritage.

Other national favorites are equally popular: samsa, a flaky pastry baked in a tandoor oven; shashlik, meat grilled over open coals; and lagman, a hearty noodle dish with meat, vegetables, and spices. All reflect the Uzbek love for rich, aromatic meals generously seasoned with traditional spice blends.

Tea and sweets also hold a special place in Uzbek food culture. Green tea is the most widely consumed beverage, enjoyed year-round both at home and in traditional tea houses, known as chaykhanas. It is often served alongside sweets such as navat (sugar crystals), chak-chak (crispy dough drizzled with honey syrup), and halva made from roasted, ground sunflower or sesame seeds blended with caramel.

The international popularity of Uzbek cuisine continues to grow. Culinary festivals dedicated to Uzbek food are held in cities around the world, including the Uzbek Culture and Food Festival, which took place in the United Kingdom in June 2023, 2024, and 2025. In cities like New York, London, Milan, Dubai, and Moscow, signature Uzbek restaurants attract growing numbers of diners. Some are featured in Yelp’s top listings, mentioned in the Michelin Guide, or highlighted in Vogue. Still, to truly appreciate the flavors and traditions behind these iconic dishes, there is no better place than Uzbekistan itself – where this culinary heritage has been passed down and perfected over centuries.

Visual Arts of Uzbekistan

The earliest surviving examples of Uzbek visual art are petroglyphs dating back 15,000 years. These engravings, which depict animals and hunting scenes, offer a glimpse into the history, beliefs, and daily life of early peoples in the region. They can be found in locations such as Zarautsoy (Surkhandarya), where many of the petroglyphs remain intact. However, due to its remote setting, the site receives relatively few visitors. Far more accessible are the ancient petroglyphs of Hojikent, located just an hour’s drive from Tashkent.

The medieval period saw the development of monumental painting, miniatures, decorative ornamentation, and calligraphy. Among these, miniature painting stands out for its detail and vibrancy – richly colored illustrations that portray scenes from literature and everyday life in the Islamic East. This refined art form reached its height under the Timurid dynasty, particularly through the work of Kamoliddin Bekhzod (1455–1535), one of the most celebrated artists of the era. Recognized for its vivid style and cultural value, miniature painting has been inscribed on UNESCO’s list of intangible cultural heritage. Also included is the art of nakkoshlik (also known as tazhib) – traditional ornamental painting using gold leaf and gilded pigments.

Some of the oldest examples of medieval art in Uzbekistan are the frescoes from Afrasiab and Varakhsha, dating from the 7th–8th centuries. These large-scale works captivate with their themes and composition. They have been displayed both in Uzbekistan and internationally, including at the Louvre (in the exhibition Splendeurs des oasis d'Ouzbékistan, 2022–2023) and the British Museum (as part of Silk Roads, 2024–2025).

In recent decades, contemporary artistic movements have also taken root in Uzbekistan. Today, the country's art scene blends national traditions with modern influences, resulting in a dynamic fusion of styles. Major tourist cities regularly host exhibitions and festivals, such as the Regeneration Art Fest for young artists in Tashkent (2024), and the Biennale of Contemporary Art in Bukhara (September–November 2025).

Crafts of Uzbekistan

For centuries, the secrets of silk weaving, ceramics, miniature painting, and national embroidery such as suzani have been passed down from generation to generation in Uzbekistan. These traditional crafts are considered cultural treasures, widely recognized by the international community and protected under UNESCO heritage programs.

Today, as you stroll through the historic streets of Uzbek cities, it’s not uncommon to meet artisans from families with six or even eight generations of master craftsmen. Many still work entirely by hand, using time-honored techniques. They are often eager to share the stories behind their craft and frequently host workshops, offering visitors a chance to experience these living traditions firsthand.

The shapes and patterns of Uzbek handicrafts are rich in symbolism. Patterned ceramics, embroidered bedspreads, animal figurines, and metal amulets often carry layered meanings. These objects, while functional, are also infused with cultural significance – symbols of happiness, harmony, protection from the evil eye, prosperity, family continuity, and good health.

Many of Uzbekistan’s most prominent artisans, such as Akbar Rakhimov, Alisher Nazirov, Madina Kasimbaeva, and Sabina Burhanova, regularly participate in exhibitions across Europe, the United States, and Japan. Their work is featured in respected directories and online platforms, including the Homo Faber Guide and Novica. Their creations are also showcased at major cultural events – most notably the Silk and Spices international festival in Bukhara. This annual celebration draws thousands of artisans, designers, and musicians, as well as tens of thousands of guests from around the world.

Fashion and Design in Uzbekistan

Eco-fashion and ethnic design play a key role in Uzbekistan’s fashion industry. Designers often work with natural, eco-friendly Uzbek fabrics and dyes, while drawing inspiration from local embroidery techniques and traditional garments – including scarves, headwear such as tubeteikas, and the iconic chapan robe. These elements frequently appear in collections that blend national heritage with contemporary aesthetics.

Photo by Joe Schildhorn/BFA.com

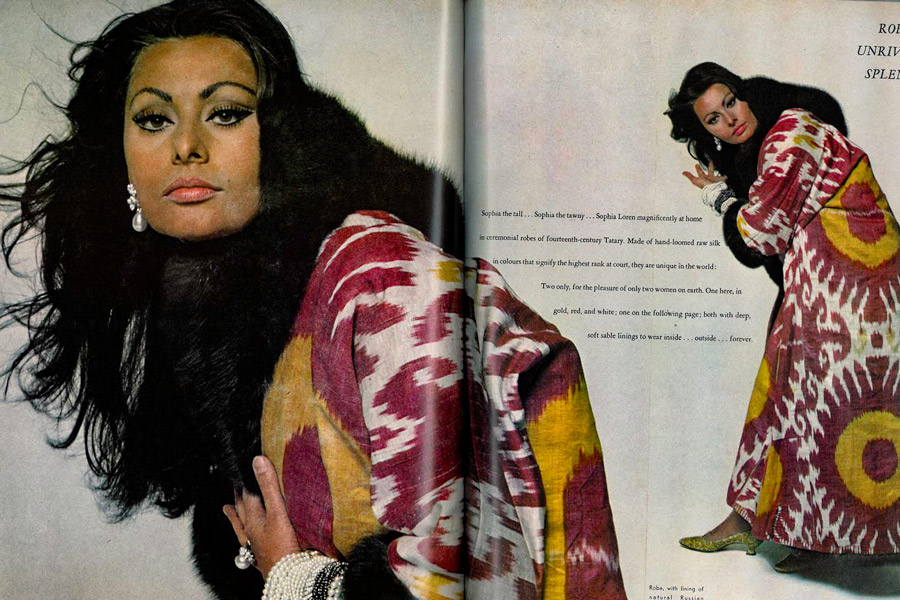

Since the 1960s – when Sophia Loren was famously photographed for Vogue wearing a traditional chapan – Uzbek motifs have gained global recognition in the fashion world. Among the most celebrated is ikat, a complex textile technique in which threads are dyed prior to weaving to form intricate patterns. This method is used to create two of Uzbekistan’s most famous fabrics: khan-atlas, made of silk, and adras, woven from cotton.

Both khan-atlas and adras have featured in the modern collections of internationally renowned designers and fashion houses, including Armani, Oscar de la Renta, and Fendi. These fabrics have also been worn by celebrities such as Cameron Diaz, Zoë Kravitz, and Kristen Stewart – further cementing Uzbekistan’s place on the global fashion map.

Uzbekistan’s Intangible Cultural Heritage

Famous Uzbek Scientists and Thinkers

Uzbekistan’s spiritual and intellectual heritage is closely tied to the legacy of great scholars and thinkers of the medieval Islamic world. These figures made groundbreaking contributions not only to the development of Uzbek culture, but also to global science, philosophy, and the arts. Many of their ideas were centuries ahead of their time.

Muhammad al-Khwarizmi (c. 780–850), a mathematician, astronomer, and geographer from Khorezm, authored Al-Jabr, the foundational work that gave algebra its name and established its basic principles.

Abu Nasr al-Farabi (872–950), often called the “Aristotle of the East,” systematized the works of ancient Greek philosophers and wrote extensively on logic, mathematics, music, and philosophy.

Abu Rayhan al-Biruni (973–1048), a polymath from Khorezm, produced influential works on astronomy, geography, and history. He calculated the Earth’s circumference with remarkable precision and described the planet as spherical.

Avicenna (Abu Ali ibn Sina, 980–1037), a physician and philosopher from Bukhara, authored The Canon of Medicine, which remained a central medical text in both the Islamic world and Europe for centuries.

Ulugh Beg (Mirza Muhammad Taragay, 1394–1449), grandson of Tamerlane, was a renowned astronomer and mathematician. He established an observatory in Samarkand and created one of the most accurate star catalogs of his time.

All of these scholars lived and worked in regions that lay along the Silk Road until the 16th century. The legacy of al-Khwarizmi, al-Farabi, al-Biruni, Avicenna, Ulugh Beg, and their contemporaries remains a vital part of Uzbekistan’s cultural identity and the broader heritage of human knowledge.

Uzbek Music

Uzbek music is best known for its classical genres, particularly the makoms. Among these, Shashmakom – a six-part cycle originating from Bukhara – is especially prominent. Over the years, it has been inscribed on UNESCO’s list of intangible cultural heritage, along with other traditions such as katta ashula (a form of large-scale vocal music) and the art of the bahshi – storytellers who perform epic dastans. In 2024, another element was added to this list: the art of making and playing the rubab, one of Uzbekistan’s oldest and most distinctive musical instruments.

Various forms of traditional music are still deeply embedded in daily life and are regularly performed at concerts and festivals. One of the most notable events is Sharq Taronalari (“Melodies of the East”), an international music festival held biennially in Samarkand.

Contemporary music also holds a strong presence in Uzbekistan. Jazz – including Uzbek interpretations – as well as rock and electronic music continue to evolve. Pop concerts featuring both local and international artists are a regular part of the cultural calendar.

One of the country’s most innovative music events is the Stikhia festival – a multidisciplinary celebration of electronic music, art, and science. Since 2017, it has been held annually in Muynak (Karakalpakstan) with the support of the Ministry of Ecology. The setting is unique: a desert landscape on the former bed of the Aral Sea. The festival blends electronic sets with art installations, lectures, and workshops, drawing over a thousand visitors from around the world each year.

Held in extreme natural conditions where participants create a temporary cultural community, Stihia is often compared to the American Burning Man festival in Nevada. However, it differs in scale, accessibility, and its distinct focus on Uzbekistan culture and ecological themes.

Uzbek Dances

Uzbekistan is renowned for its colorful and deeply rooted dance culture. Lively and expressive, dance is an essential feature of every celebration. Across the country, styles vary significantly by region: Bukhara and Fergana are known for graceful, flowing movements, while dances from Khorezm are bold and dynamic.

The most iconic is the Khorezm Lazgi, recognized by UNESCO as part of the world’s intangible cultural heritage. Celebrated for its energy and originality, Lazgi remains highly popular today and is performed in cities across Uzbekistan. It has also inspired a modern ballet production, Lazgi – Dance of the Soul and Love, which has been successfully staged in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Beijing, Dubai, and beyond.

Theater and Cinema in Uzbekistan

Watching a film or attending a theater performance can offer deeper insight into Uzbekistan’s culture, daily life, and traditions. Among the most well-known films reflecting the country’s history and society are the classics The Whole Mahalla Talks About It (1960), Alisher Navoi (1947), and The Adventures of Nasreddin (1946), as well as more recent productions like Super Sister-in-Law (2008).

Uzbekistan’s theaters, particularly the National Drama Theater, feature a rich repertoire of original plays such as Bay and Batrak, Amir Temur, and Usmon Nosir, which explore both everyday life and the stories of historical figures. For audiences who do not speak Uzbek, classical ballets like Giselle and Swan Lake are performed at the Alisher Navoi Theater. The same venue also stages modern interpretations of classical operas in their original languages, including Carmen, Rigoletto, and L'elisir d'amore.

For more experimental productions, the independent Ilkhom Theater in Tashkent is known for its bold, unconventional performances. Many of its shows, such as White White Black Stork, Dog’s Heart, and Underground Girls, are presented with English subtitles, making them accessible to international audiences.

Religion

Uzbekistan is a secular state, yet religion continues to play a meaningful role in the country’s cultural life. The dominant faith is Sunni Islam, practiced by over 90% of the population.

Islamic traditions are deeply woven into daily life. At dawn, cities echo with the call to prayer (adhan), and many residents observe daily prayers (namaz) and embrace values such as honesty, modesty, and compassion, which are central to Islamic teaching.

Other religions are also represented in Uzbekistan, including Christianity (both Orthodox and Catholic) and Judaism. In earlier historical periods, Zoroastrianism and Buddhism also had a strong presence. Although these faiths no longer have active followers in modern Uzbekistan, their cultural legacy is still visible. The Humo bird, a national symbol, and the spring holiday Navruz both have Zoroastrian origins. Archaeological discoveries further reflect this layered past – from the remains of ancient Zoroastrian temples across the country to the Buddhist complexes of Karatapa and Fayaz-Tepa in Termez (Surkhandarya Region).

This diversity of beliefs has contributed to Uzbekistan’s rich, multi-layered heritage – a cultural mosaic shaped by centuries of spiritual traditions.

Language and Literature of Uzbekistan

The modern Uzbek language belongs to the Turkic language group. It developed from Chagatai, a literary language whose tradition is considered to have been founded by the 15th-century poet Alisher Navoi. Today, several regional dialects of Uzbek exist, with the Fergana dialect regarded as the standard for literary use.

Interestingly, the Uzbek language is most similar in vocabulary and grammar to Uyghur, despite the geographical distance between Uzbek speakers and the Uyghur population in Xinjiang, China. Linguistically, Uyghur is closer to Uzbek than to neighboring Turkic languages such as Kazakh or Kyrgyz.

Uzbek literature includes a wide variety of genres – from humorous askia (verbal duels of wit) and folktales about Khoja Nasreddin, to epic dastans (oral poems), several of which are recognized by UNESCO as intangible cultural heritage.

Uzbekistan has produced many influential poets and writers throughout its history. Among them, Alisher Navoi (1441–1501) is considered the founder of Chagatai literature. His most renowned work is the Khamsa, a set of five epic poems modeled after Persian literary traditions.

Babur (1483–1530), a poet, statesman, and descendant of Timur, is best remembered for the Baburnama – a collection of memoirs that offers valuable insights into history, culture, and daily life in Central Asia.

Fitrat (1886–1938), a leading voice of the early 20th-century Jadid reform movement, was a prolific writer and cultural theorist. His legacy includes treatises on language and society, journalistic essays, and the play Abulfaizhon.

Abdulla Qadiri (1894–1938), considered the founder of the Uzbek novel, is known for his landmark works Gone Days and Scorpion from the Altar, both regarded as masterpieces of Uzbek prose.

Gafur Gulam (1903–1966) explored themes of war and humanism. His most celebrated works include the novella Shum Bola and the poem You Are Not an Orphan, which became symbols of resilience and compassion.

Erkin Vakhidov (1936–2016) was a leading poet of Uzbekistan’s modern literary period. In addition to his plays and poetry collections such as Breath of Dawn, his poem Ode to Man was translated into eight languages and performed at the 75th-anniversary event of the United Nations in 2020.

Abdulla Aripov (1941–2016), another celebrated poet, is best known as the author of the lyrics to Uzbekistan’s national anthem, as well as for his numerous works exploring philosophical and national themes.

The culture of Uzbekistan is a living and evolving environment. Centuries-old buildings, works of art, and ancient traditions are carefully preserved, but they are not frozen in time; instead, they are combined with modern visions and trends. For example, the Eternal City ethnopark in the Silk Road complex in Samarkand (2022) and the Arda Khiva tourist complex in Khiva (2024) are reinterpretations of heritage.

Uzbek Culture in Everyday Life

Centuries-old customs continue to shape everyday life in Uzbekistan, remaining a vital part of the nation’s contemporary identity. Their influence is most evident in mahallas - traditional neighborhood communities often described as the “heart of Uzbek society”.

In the mahalla, neighbors maintain such close ties that they often see each other as extended family. Children play together in the streets, elders handle communal matters, and daily life revolves around gatherings on topchans – open-air sitting areas in courtyards furnished with low tables, cushions, and blankets. These scenes create an atmosphere that is both intimate and uniquely Uzbek.

Interpersonal relationships and traditional Eastern values hold great significance. Chief among them is the renowned Uzbek hospitality, considered one of the country’s defining cultural traits. In every home, guests are honored with tea, flatbread, fruit, and sweets – a gesture of warmth and generosity deeply rooted in national identity.

Respect for elders is another cornerstone of Uzbek society. It is customary to speak politely with older people, offer them the first word during gatherings, and give up one’s seat for them on public transport.

Daily life in Uzbekistan also reflects an Eastern appreciation for balance and calm. The rhythm of life tends to be measured and harmonious, encouraging moments of reflection and inner peace.

At the same time, hard work and discipline are deeply valued. Many begin their workday early, and labor is traditionally associated with dignity, honesty, and the well-being of the family.

Festive Culture of Uzbekistan

Festivals and celebrations are among the most vibrant expressions of Uzbekistan’s cultural identity. Holidays are celebrated with great enthusiasm – streets fill with the sounds of traditional wind instruments like karnays and surnays, people wear national costumes, and dancing becomes a central part of the festivities.

The oldest and most beloved holiday is Navruz, celebrated on March 21, the spring equinox. This colorful celebration features music, dancing, and the communal preparation of sumalak, a ritual dish made from sprouted wheat. Navruz and its associated customs are recognized by UNESCO as intangible cultural heritage shared by Uzbekistan and several other countries – including Azerbaijan, Iran, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Turkey.

Religious traditions also hold a significant place in Uzbek culture. The sacred month of Ramadan, along with the holidays Ramadan Khait and Kurban Khait, are widely observed. A key aspect of these observances is iftar, the evening meal that breaks the daily fast. As a social and spiritual ritual that fosters family bonds, community unity, and charitable traditions, iftar has also been inscribed by UNESCO as part of the world’s intangible cultural heritage.

Equally important are family celebrations, particularly weddings and rites marking key stages in a child’s life, such as beshik-tuy (cradle celebration) and sunnat-tuy (circumcision ceremony).

Uzbek wedding culture is especially rich and elaborate, known for its multitude of symbolic traditions. The guest list often numbers in the hundreds – sometimes over 500 – and the celebrations are marked by vibrant customs such as the nikoh-tuy (religious wedding ceremony), the bride’s greeting known as kelin salom, and the performance of the famous wedding song Yor-yor.

Past and Present in Harmony: Uzbekistan’s Evolving Culture

The culture of Uzbekistan is not static – it is a dynamic and evolving force. While centuries-old buildings, artworks, and traditions are carefully preserved, they are continuously reinterpreted through modern perspectives. Recent projects such as the Eternal City ethnopark at the Silk Road complex in Samarkand (2022) and the Arda Khiva tourist complex in Khiva (2025) exemplify how heritage can be thoughtfully reimagined.

A striking example of this cultural renewal is the Uzbekistan pavilion Garden of Knowledge, presented at Expo 2025 in Osaka, Japan. Drawing inspiration from Khiva’s architecture and the majolica of Bukhara, and enriched with motifs from Uzbek folk crafts, the pavilion combines traditional elements with contemporary design in a visually compelling way.

The project was developed by Atelier Brückner at the initiative of the Uzbekistan Culture and Arts Development Foundation, an organization that continues to champion innovative projects in the fields of visual arts, music, and architecture across the country.