Hand embroidery in Uzbekistan is an ancient craft passed down from generation to generation for centuries and remains one of the most expressive forms of Uzbek culture. Its vivid colors, confident stitches, and meaningful symbolism reveal a deep history and the distinctive regional character embedded in every piece.

This tradition has long been inseparable from folk clothing and is equally present in home décor. Embroidered bedspreads, prayer rugs, tablecloths, and other textiles remain a familiar part of daily life. Girls and women still create these items with deliberate care, holding to the belief that age-old patterns can guard the household and bring good fortune to its owner.

The uniqueness of Uzbek embroidery was highlighted by the exhibition “Heritage in Stitches: A Journey through the Embroidery and Sewing Traditions of Uzbekistan,” held in Samarkand in 2025 as part of the 43rd session of the UNESCO General Conference.

The Main Types and Regional Styles of Uzbek Embroidery

The main and most distinctive type of Uzbek embroidery is the decorative panel known as suzani. This term comes from the Persian word “suzan” (سوزن), which literally means “needle.” Suzani were once found in almost every home in Uzbekistan, serving as carpets, bedspreads, or tablecloths.

These large canvases have developed a recognizable stylistic language that is now also applied to smaller garments and household objects. As a result, suzani has become almost synonymous with Uzbek embroidery as a whole.

Suzani are divided into three principal local styles: Bukhara, Samarkand, and Fergana. The Bukhara style resembles Nurata, Shakhrisabz, and Kitab embroidery, while the Samarkand style is similar to Tashkent, Jizzakh, and Baysun work. Regional types of suzane differ in their motifs, overall composition, density of the pattern, and color palette.

Bukhara Embroidery

Bukhara has long been a center of arts and crafts, and this heritage is clearly reflected in the richness of its embroidery. It is easily recognized by its intricate, highly controlled patterns that cover nearly the entire surface of the fabric, as well as by its characteristic palette built around a light background with red and green ornaments.

Islamic artistic traditions play a defining role in Bukhara embroidery in Uzbekistan, most notably through the use of the “islami” floral motif and stylized flower forms. In terms of composition, these suzani fall into two categories: symmetrical designs built around diamond-shaped layouts and centric arrangements with a medallion placed at the center.

Nurata Embroidery

The Nurata school is one of the most recognizable among the various types of embroidery in Uzbekistan. Its style resembles that of Bukhara and is characterized by numerous floral patterns on a light background. However, in this tradition they appear as bushes or bouquets, rendered with notable realism. This feature creates the most striking distinction between Nurata and other styles: instead of stylized floral abstractions, it portrays local carnations, irises, cotton flowers, or cherries. Birds or animals often accompany these botanical motifs.

In most cases, Nurata embroidery includes a central element in the shape of an eight-pointed star, framed on four sides by floral designs. This popular composition is known among local people as “four branches and one moon”.

Each pattern of Nurata embroidery is marked by the simplicity and individuality of its forms and proportions, which can sometimes give the overall composition a slight asymmetry. The palette is quite varied, yet the tones chosen tend to be calm and subdued.

Interestingly, many works contain a deliberate “mistake” in their color scheme — for example, a green flower or a red leaf. This device carries a religious meaning and serves as a reminder that humans are imperfect and that only God can create flawless colors and shapes.

Shakhrisabz Embroidery

The ornamentation of Shakhrisabz embroidery also reflects the influence of the Bukhara style, a connection explained by the city’s long history within the Bukhara Emirate.

A defining feature of Shakhrisabz embroidery is its exceptionally dense patterning, which leaves almost no visible background. Another characteristic trait is the use of different colored fabrics as the base, including purple, yellow, and green.

Some suzani include distinctive elements of Zoroastrian symbolism, such as oil lamps framed by floral motifs.

Samarkand Embroidery

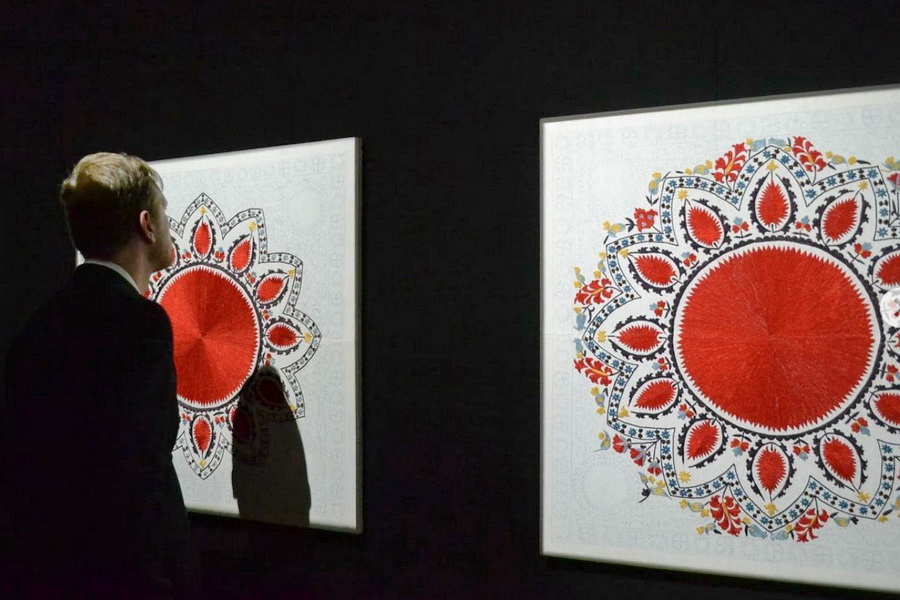

The Samarkand tradition is defined by its streamlined compositions built around large circles and rosettes framed by serrated leafy hoops. The color palette is typically restrained, relying on red and black set against a white background. This distinctive combination emerged toward the end of the 19th century, replacing the earlier use of raspberry and green tones.

Tashkent Embroidery

One of the most distinctive embroidery styles in Uzbekistan developed in Tashkent. It differs from other regional schools in its ornamentation, structure, symbols, and even its terminology. Decorative embroidery here is known as “palak” (literally “sky”). Palaks are dominated by red tones, marked by dense stitching, and distinguished by astral symbols featuring large circles that represent planets.

The tradition of creating these cosmological suzani disappeared entirely in the 20th century. It was revived only at the beginning of the 21st century, when the skilled craftswoman Madina Kasimbaeva began producing new works inspired by historical books, museum collections, and the guidance of art specialists.

Another form of Tashkent embroidery is “gulkurpa”, whose composition is arranged as a central star or circle with flowering branches, leaving substantial areas of plain, unembroidered fabric visible.

Fergana Embroidery

Fergana embroidery is marked by its refined graphic style and restrained ornamentation, which leaves generous areas of open background. Most often, Fergana suzani are stitched on dark silk fabrics. Their patterns feature thin branches, rosettes, and bouquets rendered in contrasting colors. Fergana embroidery brings together the elegance of plant motifs and the presence of archaic symbols. The latter appears in the inclusion of ornamentation drawn from nomadic cultures, such as horn motifs or swirling rosettes.

The Symbolism and Mystique of Uzbek Embroidery

Suzani is one of the most enigmatic and symbolically charged forms of decorative art in Uzbekistan. It preserves many ancient messages; for example, certain ornaments relate to the cult of planets and early deities that existed in Central Asia before the spread of Islam. These ideas appear in archaic geometric motifs such as circles, rhombuses, and swirling rosettes.

Plant and floral designs, by contrast, are more closely aligned with Islamic art and carry religious meaning, evoking the idea of a paradise garden on earth. Each element within such compositions has its own distinct significance. Pomegranates, for instance, symbolize fertility, while almonds and peppers serve as protective talismans.

Magical rituals have also been linked to Uzbek suzani art. In the past, only selected women known as “chizmakash” were permitted to create the initial designs, and they underwent a special initiation rite. Each artist chose her successor, who, after receiving a blessing, was bound to continue the craft. The patron saint of artists was believed to be the founder of the Sufi order, Bahouddin Nakshband, whose name literally means “pattern maker”.

Uzbek Embroidery: Origins, Practice, and Tradition

The roots of this art reach back to ancient times, when all women and girls in every neighborhood of Uzbekistan practiced embroidery. From childhood they prepared their dowries, and later, when they became mothers, they taught the craft to their daughters. In this way, the art of Uzbek embroidery was passed down from generation to generation for hundreds of years.

Embroidery is a discipline that demands patience and skill. Each square centimeter of ornamentation requires dozens of stitches worked in various techniques. As a result, creating a large piece could take master craftswomen up to eight years. In the past, textiles were embroidered for a girl’s wedding, and if the work was not finished in time, relatives and neighbors would come to help.

Women traditionally used cotton (calico) or silk fabrics as the base, along with hand-made silk threads dyed with natural pigments that helped preserve their color and brightness for decades or even centuries.

Embroiderers typically learned from other craftswomen, but they also relied on special tools for everyday practice. Known as nuska-don, these aids consisted of fabric pieces sewn together like a book, containing basic embroidery patterns. Today they can be seen in the Museum of Arts in Tashkent.

Ancient Uzbek embroidery is preserved in many museums across Uzbekistan and around the world. For example, it is represented in the State Museum of Applied Arts in Tashkent, the Minneapolis Institute of Art in the United States, the Powerhouse Museum in Australia, and the Museum of Islamic Culture in Hawaii.

The Revival and Global Rise of Uzbek Suzani

Photo: Instagram / Madina Kasimbaeva

In the 20th century, traditional types of Uzbek suzani began to fade from everyday life as mass machine production expanded. Yet the ancient techniques preserved by a small group of craftswomen were fully revived at the turn of the century. Today, they are being carried forward by a new generation of embroiderers across different regions of Uzbekistan.

Many craftswomen adhere to age-old methods, working with natural fabrics and threads—mainly silk and wool — and using only materials that would have been available before the early 20th century. Some even refuse to draw circles with a bow compass, considering it an intrusion on centuries-old Uzbek embroidery practices.

One of the key contemporary trends is the growing global visibility of Uzbek embroidery. Suzani are now featured at international exhibitions, festivals, museums, auctions, and even in the wardrobes of statesmen and celebrities around the world. In this way, embroidery has become one of the most prominent and representative elements of Uzbek culture.

Suzani embroidered in Uzbekistan are held and exhibited in many cities worldwide. The 2023 exhibition project “9 Moons,” shown in Berlin and London, presented suzani from the family collection of artist Aziza Kadiri. Works by the Tashkent craftswoman Madina Kasimbaeva are represented in the British Museum and in private collections; for instance, two of her chapan robes were acquired by American designer Iris Apfel.

Uzbek embroidery reaches impressive prices at auctions such as Sotheby’s and Rippon Boswell. One suzani embroidered in Shakhrisabz sold for about $160,000, making it the most expensive Uzbek textile ever sold.

In addition, artisans from Uzbekistan present their exclusive works on international online platforms. For example, Muhabbat Kuchkarova, a hereditary suzani embroiderer from Bukhara, and her daughter Aziza Toshieva are registered on Etsy, an international online marketplace for handmade and vintage goods. The women of the Kuchkarov family have practiced Uzbek embroidery for five generations. They now run their own workshop near Bukhara, where several hundred craftswomen work.

In Uzbekistan, unique suzani can be viewed and purchased at numerous festivals and craft fairs; at bazaars, especially the well-known Chorsu in Tashkent; and in workshops and showrooms, including Human House and Suzani by Kasimbaeva in the capital, and the Happy Bird Gallery in Samarkand.