China is home to a wide range of languages and dialects, each rooted in its own historical and cultural context. Their origins extend deep into the past: found in the legends of family communities, the words of early philosophers recorded on delicate mulberry paper, and the resonant singing once heard on the stages of traditional opera houses.

Today, travellers have a unique opportunity to experience the diversity of Chinese languages firsthand, gaining insight into their structures, sounds, and cultural meanings through everyday communication. Each language and each dialect carries its own character, symbolism, and patterns of thought, shaping traditions, inspiring stories, and fostering a sense of cultural belonging. In this guide, we will explore the country’s main linguistic traditions, trace their ties to culture, and offer practical advice for those wishing to communicate confidently while travelling in China.

Evolution of Chinese Languages: A Brief History

Over the course of thousands of years, Chinese languages have evolved from their earliest forms into a sophisticated system characterised by an complex writing tradition and layered phonetic features. This long evolution reflects the influence of various historical periods, each leaving its distinct mark on the sound, structure, and linguistic character of the language spoken today.

Origins of the Chinese Language

There is still ongoing debate among experts, and no consensus has yet been reached to confirm that Sinitic languages share a common ancestor with Tibeto-Burman languages, a group of languages that all descend from Proto-Sino-Tibetan.

Pre-Classical period (1300–500 BCE)

Archaic (Old) Chinese represents the earliest known form of the written language as attested during the Shang dynasty (around 1250 BCE). During this period, inscriptions were carved onto divination bones and turtle shells, which played a central role in mythological ritual practices and were used to forecast future events. Visitors can examine some of these artefacts at the Yinxu Museum in Anyang, Henan province, which has a significant collection.

Old Chinese encompasses the initial forms of Chinese writing and acts as the linguistic foundation for later variations. Calligraphy is closely connected to the written form of the language and the evolution of Chinese scripts.

The Western Zhou dynasty (1046–771 BCE) is the source of later material monuments, which include collections of poetry and prose. Writing gradually expanded beyond ritual divination and became a means of recording historical events, genealogies, and state ceremonies. This evolution was influenced by political and social changes during the Zhou dynasty.

Development of Middle and Late Archaic Chinese

Middle Archaic Chinese was used by some of the earliest schools influenced by Confucius (551–479 BCE). Significant linguistic modifications took place over time and became even more evident in Late Archaic Chinese. The language spread through religion and philosophies of life. Notably, it is present in the writings of Mencius (372–289 BCE) and Zhuangzi (369–286 BCE), two influential Confucian and Taoist writers, as well as those of other significant philosophers. The language used in their works became a reference point for later generations and has been preserved not only through canonical texts but also in material form. More than 370 ancient artifacts related to the Analects of Confucius are currently on display at the Confucius Museum in Qufu (孔子博物馆), Shandong Province.

The phonetic system of Old Chinese differed markedly from that of modern Chinese. According to scholarly reconstructions, speech during that era may have sounded harsher, as many words began with consonant clusters that have since disappeared. Tones, which are fundamental to modern Chinese languages, had not yet developed, resulting in a more fluid and less regulated melodic quality.

Archaic Chinese was also marked by a strong tendency towards standardisation.

Qin Shi Huang (秦始皇) (221–210 BCE), recognised as the first emperor of China, played a major role in unifying the nation. He standardised writing, language, currency, weights, and measures and is often referred to as the father of the Great Wall of China.

In the 1st century, early dialects did exist, a fact documented in the earliest dictionary of Chinese dialects, known as Fangyan (方言), compiled by the philosopher Yang Xiong (揚雄) (53 BCE–18 CE). Each ancient kingdom maintained its own variant of speech.

Mediaeval Chinese Language Development

From the 2nd century BCE to the 14th century CE, the Silk Road played a major role for cultural exchanges, which included language and writing systems.

As cultural, political, and social structures became increasingly more complex, Archaic Chinese gradually transitioned into what linguists refer to as Middle Chinese (sometimes also called Ancient Chinese). One of the key sources for reconstructing the sound system of this period is the Qieyun rime dictionary (切韻), first published in 601 and later revised in expanded editions, including the Guangyun (1008).

In Middle Chinese, the phonetic system saw considerable enhancement characterised by a broader range of consonants and vowels. Four tones were clearly distinguished, first described by the Chinese scholar Shen Yue (沈约) (441-513). Syllable structure also became more refined. Many of the complex consonant clusters characteristic of archaic Chinese gradually disappeared.

Middle Chinese serves as the basis for a diverse array of dialects that emerged as a result of migration, administrative change, and cultural transformation. This stage in the language’s development laid the foundations for both regional dialects and the modern standardised forms of the language spoken today.

Modern Chinese Language

Over time, numerous regional dialects emerged and reached communities from different parts of the country, highlighting the need for a shared form of speech that could be widely understood. By the late imperial period, following the relocation of the capital to Beijing under the Ming dynasty and later the Qing dynasty, northern varieties of Chinese gained prominence, with the Beijing dialect gradually establishing itself as the dominant reference.

After the revolutionary transformations of the early 20th century, efforts towards linguistic unification intensified. In 1932, a standardised “national language” based on the Beijing dialect was officially adopted. In 1955–1956, this language was named Putonghua (普通话), commonly known as Standard Mandarin, which literally translates to “common speech” in the People’s Republic of China. It became the standard for education, the media, public life, and official communication.

Modern Standard Chinese is characterised by relatively simple, codified phonetics and grammar. Syllables typically consist of a consonant followed by a vowel, sometimes ending with “-n” or “-ng”, which reflects a significant simplification compared to earlier stages of the language. Consequently, Putonghua serves as a linguistic bridge across China, enabling communication between speakers of different regional dialects despite their considerable diversity. Additionally, Modern Standard Chinese is one of the six official languages of the United Nations.

Chinese Languages, Dialects and Writing Systems Explained

There are more than 200 dialects in China, which linguists typically classify into ten major language families. Each of these families is further divided into numerous regional branches, shaped by local history, traditions, and lifestyles. This section focuses on the most prevalent languages and dialects that have significantly contributed to shaping China’s modern linguistic landscape.

Understanding Mandarin (Putonghua)

With about 800 million speakers, Standard Mandarin (官话) is the official language of the People's Republic of China (PRC), Taiwan and Singapore. Shaped by northern dialects, it encompasses several major regional varieties.

Mandarin is not a uniform language and varies across different regions. Beijing Mandarin (北京官话) serves as the foundation for the modern standard language, while Southwestern Mandarin (西南官话) is spoken in Sichuan, Chongqing, and parts of Guizhou and Yunnan. Northeastern Mandarin (东北官话), spoken in the provinces of Heilongjiang, Jilin, Liaoning, and parts of Inner Mongolia, preserves distinctive phonetic and lexical features. Common characteristics among Mandarin dialects include a relatively straightforward tonal system, a prevalence of monosyllabic roots, and a broad shared vocabulary that facilitates mutual intelligibility across vast areas. However, noticeable differences in pronunciation and intonation between western, northeastern, and central varieties remain clearly perceptible and continue to shape local linguistic identities.

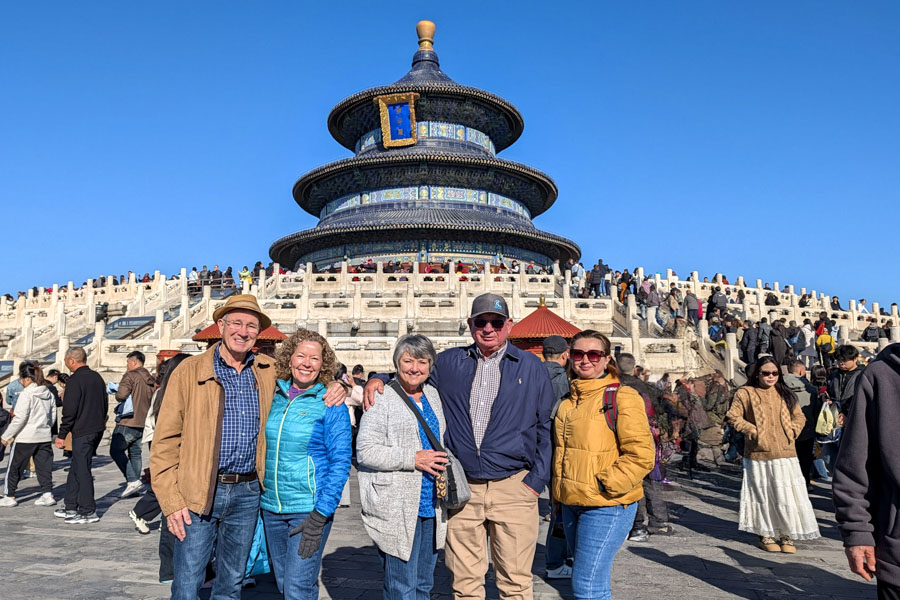

Visitors can enjoy its tones at the Peking Opera or in cinemas across Beijing.

Cantonese Chinese: Varieties and Linguistic Traits

In southern China, Cantonese (粤语), also referred to as Yue (粤语 / yuhtyúh) Chinese, or Guangzhou dialect (廣東話), holds a distinctive position in the country’s linguistic landscape. It is widely spoken in the provinces of Guangdong and Guangxi, as well as in Hong Kong and Macao, where it serves as the primary language for everyday communication and a fundamental aspect of local cultural identity. Cantonese differs significantly from standard Putonghua, notably in its tonal system, which traditionally features a larger inventory of up to nine tones. Within Cantonese, several regional varieties exist, including several regional varieties such as Taishan (Si-yi), Yangjiang (Gao-Yang), Nanning (Qin-Lian), and the Guangxi–Guangdong border (Gou–Lou), which differ mainly in pronunciation and specific lexical features while remaining mutually intelligible to speakers.

Other Major Chinese Dialects

While Mandarin and Cantonese dominate much of northern and southern China, a number of other major language groups further illustrate the country’s deep regional diversity. Wu (吴语) is spoken in and around the economically powerful cities of the Yangtze River Delta, including Shanghai, parts of Jiangsu province, and Zhejiang. It differs from Mandarin due to its more complex phonetic system and a wide variety of local dialects, such as the Jinhui dialect, which is noted for its extensive vowel inventory.

The greatest internal diversity is found within the Min languages (闽语), concentrated in Fujian province and extending to Eastern Guangdong, as well as Hainan Island and the Leizhou Peninsula. In this region, local dialects can differ so dramatically in pronunciation and vocabulary that they are mutually unintelligible, even among those belonging to the same group. Hakka (客家话), on the other hand, represents the speech of the Hakka people across much of southern China. It is notably spoken at the crossroads of Guangdong, Fujian, Jiangxi, Guangxi, Hainan, Sichuan, Hunan, and Guizhou and is recognised for preserving ancient phonetic features that are no longer present in Mandarin. Jin (晋语), once classified as a branch of Mandarin, is now recognised as a distinct northern group primarily spoken in Shanxi and surrounding areas. It is characterised by a complex system of tone sandhi, a phonological change that alters tones in connected speech.

Gan (贛語) predominates in Jiangxi province and neighbouring regions, where its sound patterns and vocabulary exhibit similarities to Hakka, reflecting the long-standing historical interactions between these communities. A similar phenomenon can be observed in Xiang (湘) in Hunan, where southern linguistic traits coexist with archaic features and distinctive phonetics, including a tonal system that ranges from five to seven tones depending on specific locality. Huizhou (徽语), also known as Hui Chinese, occupies a special position as a compact yet resilient group of dialects spoken in the provinces of southern Anhui, northeastern Jiangxi, and western Zhejiang. This dialect group combines elements of Wu and Gan due to historical interaction in mountainous areas. Finally, Pinghua (平话) is primarily found in Guangxi and Hunan, appearing as a distinct variety with its own internal divisions into northern and southern subgroups, each shaped by interactions with neighbouring dialects.

Chinese Writing Systems: Traditional and Simplified

There are two main writing systems in Chinese: traditional and simplified characters. Traditional characters, which developed over many centuries, are visually intricate and consist of a large number of strokes. For instance, the character for “dragon” is written as 龍 in traditional form and as 龙 in simplified form. In the mid-20th century, mainland China implemented a reform that reduced the number of strokes in many commonly used characters, making writing more accessible and speeding up the learning process. Today, simplified characters are used in mainland China, Singapore, and Malaysia, while traditional characters are still used in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macao, as well as in many overseas Chinese communities. Familiarity with both systems fosters a deeper understanding of cultural differences and enables confident reading of texts produced in various regions.

Chinese Calligraphy: More Than a Medium for Languages

Chinese calligraphy is one of the most beautiful media that has carried the words of the ancients through time to reach us today. It has long been seen as a reflection of a person’s moral character and intellectual depth. Renowned masters such as Wang Xizhi (王羲之) (303–361 CE) created works that continue to serve as enduring standards of beauty and expressive power.

For a more detailed exploration of China’s written tradition, see our comprehensive Chinese Writing Language Guide.

The Role of Language in Chinese Culture and Religion

Language in China has historically gone beyond being just a basic tool for communication; it has played a crucial role in shaping daily life, ritual practices, and broader worldviews. Understanding how language reflects values, beliefs, and social norms provides deeper understanding of the foundations of the country’s cultural life.

Language in Religious Context

In Chinese tradition, language and worldview are deeply intertwined, with everyday speech reflecting the spiritual teachings that have shaped thought patterns over centuries. Confucianism, which emphasises moral conduct, family responsibility, and social harmony, has left a lasting mark on vocabulary and daily expressions. Concepts like sincerity (诚), reverence or respectfulness (敬), and ritual propriety (礼) serve as linguistic indicators of social order and ethical behaviour.

Taoism has also impacted language using metaphors drawn from nature and ideas of inner balance. The concept of the Dao (道) and the principle of non-action (无为) are embedded in established expressions that value natural flow, gentleness, and non-coercive action. A notable example is the idiom 顺其自然 (shùn qí zìrán), which translates as “to let nature take its course”, reflecting the Taoist ideal of aligning with the natural order.

In Buddhism, language serves as a tool for expressing inner experience and the path to enlightenment. Fundamental concepts such as suffering (苦), impermanence (无常), and emptiness (空) became firmly established in philosophical and religious discourse before permeating broader cultural contexts. While Confucian terminology reinforces social roles and Taoist expressions emphasise harmony with nature, Buddhist language draws attention to the transient nature of reality and the workings of consciousness, perspectives that are evident in sermons, commentaries, and everyday reflections on life.

All those concepts are incorporated in Chinese etiquette.

The Importance of the Chinese Language in Cultural Rituals

Language plays a distinctive role in rituals that are part of everyday life. One clear example is the communal tea ceremony, which is one of China’s most beloved traditions. In this setting tea symbolises respect, harmony, and social balance. During weddings, newlyweds offer tea to their elders as a gesture of gratitude and reverence, while in casual situations, serving tea expresses goodwill and hospitality. These rituals are invariably accompanied by polite expressions, blessings, and well-wishes that enrich the ceremonial tone. Phrases like 敬茶 (to respectfully offer tea) and 请茶 (invitation to tea) convey not just actions but also a courteous way of interacting. The saying 以茶代酒 (tea instead of wine) emphasises tea’s symbolic role in traditional etiquette.

Rituals marking significant life stages bestow deep meaning on language, transforming it into a vehicle for memory, social recognition, and shared values. Traditional rites of passage, such as the coming-of-age ceremony called Chū Huā Yuán (出花园), practised in the Chaozhou region, involve formal blessings that define an individual’s social standing and their ties to ancestors, the community, and future responsibilities. The name of the ceremony, translating to “leaving the garden”, metaphorically represents the transition from childhood to adulthood, marking a young person’s step into independence.

In wedding ceremonies, the San Bai (三拜礼) – which involves the three bows ritual to express reverence first to heaven and earth, second to ancestors, and third to one another – remains a central feature. These bows are traditionally accompanied by blessings from elders or the officiant. One popular saying, 百年好合 (Bǎinián hǎo hé), “a hundred years of happy union” – encapsulates the cultural value placed on long and harmonious marriages, demonstrating how ritual language expresses collective hopes and aspirations.

Visitors who tour China during holidays, and especially at the Lunar New Year, may hear several recurring phrases, such as Xīnnián Kuàilè (新年快乐), which means "Happy New Year!" And Gōngxǐ Fācái (恭喜发财) means "Wishing You Wealth!" These phrases are often accompanied by Bào Zhūn Fú (报准福), which translates to "Wishing You Good Fortune!"

Chinese Languages in Arts and Cultural Heritage

Long before writing became widespread in China, tales of heroes, monks, and mythical beings were preserved through oral tradition – shared within families and exchanged in markets and teahouses. Chinese folklore acted as a living reservoir of collective memory, with language serving as the primary vehicle conveying historical experience, moral values, and shared worldviews.

The legend of Cangjie (仓颉), a revered figure in Chinese mythology, tells how the first Chinese characters were created. As a historian during the reign of the Yellow Emperor, Cangjie sought to improve communication beyond simple spoken words. Inspired by the natural world and its unique forms, he created a system of characters to represent ideas. His profound understanding was symbolised by his four eyes. Cangjie's perseverance ultimately laid the foundation for the written Chinese language, cementing his legacy as the father of Chinese writing.

As we explore more about China's cultural heritage, it becomes evident that language is crucial in various art forms.

The Grand Song of the Dong ethnic group, which is listed as an intangible cultural heritage by UNESCO, demonstrates how community singing, commonly held during festivals, embodies the Dong language's essence. Not only do these songs convey stories, but they also celebrate moral values and community ties.

The diversity of dialects can also be seen in Chinese theatre, the Gesar epic tradition, and traditional Peking opera, Yueju opera, Kun qu opera, Tibetan opera, and Sichuan opera.

Folk songs that resonate through the ages play an essential role in these cultural narratives. Hua'er, a musical genre originating in north-central China, is sung in local dialects and expresses the joys and hardships of rural life. These melodies are emotionally charged and depict the daily life of communities. Similarly, the Xi'an wind and percussion ensemble, which has played in China’s ancient capital of Xi’an for more than a millennium, celebrates regional diversity, showing how music and language can combine to tell stories of personal and community identity.

These magnificent performances serve as a vehicle for storytelling, combining music, physical expression, and poetry. Language is not just a means of communication but also a way of expressing regional culture and the memory of past generations. They form the cornerstone of Chinese identity.

Tips for Travellers to Practise Chinese in China

Language is an essential companion when travelling in China, and even a basic understanding of common phrases can significantly aid in communication, help navigate unfamiliar surroundings, and show respect for local culture.

Basic Phrases in Mandarin and Cantonese

Starting with a small set of everyday expressions can be immediately useful in daily interactions. Greetings such as Nǐ hǎo (你好, “hello”) and Xièxiè (谢谢, “thank you”) help create a friendly atmosphere. Phrases like Qǐngwèn… (请问…, “excuse me, may I ask…?”) allow you to address passers-by or service staff politely.

When getting around cities, knowing how to ask for directions and prices can be very helpful. Simple questions such as Zài nǎlǐ…? (在哪里…?, “Where is…?”) or Duōshǎo qián? (多少钱?, “How much is it?”), along with basic transport terms like chūzūchē (出租车, taxi) and dìtiě (地铁, metro), make navigation easier without lengthy explanations.

For travellers heading to regions where Cantonese is widely spoken, a few local phrases can be just as valuable. Expressions such as Néih hóu (你好, “hello”) and M̀h gōi (唔該, “thank you”) help establish a friendly contact in everyday situations. In Hong Kong or at markets in Guangdong province, you might also ask Bīn dou…? (邊度…?, “where…?”) or Nī go géi dō chín? (呢個幾多錢?, “how much is this?”), reflecting local speech patterns and social etiquette.

Use the table below to easily navigate the most common basic expressions.

| British English | Mandarin (Putonghua) | Cantonese |

| Hello | 你好 (Nǐ hǎo) | 你好 (Néih hóu) |

| Excuse me / Sorry | 不好意思 (Bù hǎo yìsi) | 唔好意思 (M̀h hóu yi si) |

| Thank you. | 谢谢 (Xièxie) | 多谢 (Dōjeh) |

| Please. | 多谢 (Dōjeh) | 請 (Ceng) |

| Yes. | 是 (Shì) | 系 (Haih) |

| No. | 不是 (Bú shì) | 唔系 (M̀h haih) |

| I don’t understand. | 我不懂 (Wǒ bù dǒng) | 我唔明 (Ngóh m̀h mìhng) |

| Do you speak English? | 你会说英语吗?(Nǐ huì shuō Yīngyǔ ma?) | 你识唔识讲英文?(Néih sīk m̀h sīk góng Yīngmàhn?) |

| How much is this? | 这个多少钱?(Zhège duōshǎo qián?) | 呢个几多钱?(Nī go géi dō chín?) |

| Where is the metro? | 地铁在哪里?(Dìtiě zài nǎlǐ?) | 地铁喺边?(Deih tit hái bīn?) |

| I would like this. | 我要这个 (Wǒ yào zhège) | 我要呢个 (Ngóh yiu nī go) |

Language Etiquette and Translation Tips for Travelling in China

Language etiquette is an essential part of communication in China. Proper pronunciation of tones is essential, as the same syllable can convey entirely different meanings depending on the tone used. Paying attention to intonation and context is widely regarded as a sign of respect. Politeness is equally important, and using phrases like Duìbuqǐ (对不起, “sorry, or excuse me”) can help create a positive impression and facilitate smoother interaction.

Engaging with locals on everyday topics can be the easiest way to establish connections. Conversations about food, the weather, or directions typically begin with simple exchanges and can naturally evolve into deeper discussions, providing insights into the rhythm and tone of daily communication. Speaking with people in shops, markets, teahouses, on public transport, and in other shared spaces offers valuable opportunities to practise pronunciation in real-life contexts.

It is also practical to use a translation app on your phone while travelling. Such tools are particularly useful for understanding signs, menus, and transport information, especially in areas where English is less commonly spoken. Using these apps not only helps overcome language barriers but also supports a more profound engagement with daily life and shows respect for local customs, contributing to more effective and considerate communication.