Gunpowder, also known as black powder, is one of the great turning points in world history, yet its origins lie deep in the intellectual landscape of ancient China. Developed through early experiments in alchemy, it emerged long before its global impact was understood – first as an unexpected discovery in the search for immortality, and later as a substance that reshaped warfare, political power, and the limits of human capability. Together with the compass, papermaking, and printing, it is recognised as one of China’s Four Great Inventions from imperial China, a group of achievements that influenced the course of civilisations far beyond East Asia.

Understanding gunpowder means following the journey of how three familiar ingredients have acquired extraordinary significance. This guide explores the story behind its discovery, its role in the rise of new military technologies, and the ways it altered the trajectory of states and empires. It also looks at the cultural imprint gunpowder left behind: who first revealed its potential, how it figures into modern Chinese identity, and where its history can still be encountered today. What began as an alchemical experiment ultimately became a power that helped shape the fate of humanity.

Who First Discovered Gunpowder?

The Invention of Gunpowder in China: Fire Medicine and Early Weapons

Gunpowder emerged in China around 9th century, during the Tang dynasty, not as a weapon but as the byproduct of alchemical experiments. Daoist scholars searching for an elixir of eternal life combined sulphur, saltpetre (potassium nitrate), and charcoal, and instead of a life-giving substance, they discovered a mixture that sparked, smoked, and ignited with startling force. The Chinese term for it, huo yao (火药) – “fire medicine” – reflects its origins in the pursuit of vital energy, even as the new substance revealed a far more volatile potential.

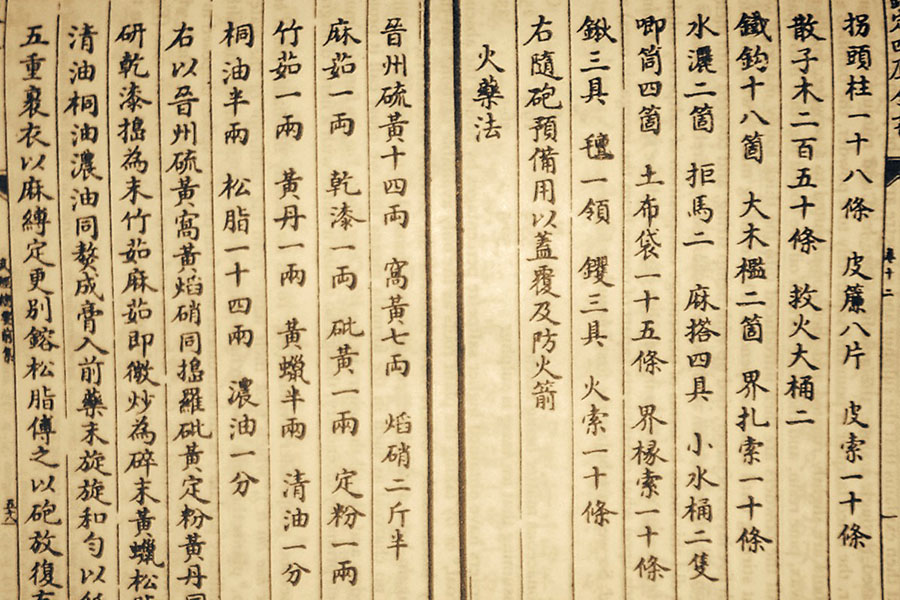

The earliest detailed descriptions of gunpowder appear in the Wujing Zongyao (武经总要), a military compendium completed in 1044. It recorded precise formulas, proportions of ingredients, and designs for early flame-projecting devices and primitive cannons capable of projecting fire across short distances. When mixed in approximately the right ratios (75% saltpetre, 15% charcoal, and 10% sulphur), it ignites quickly, generating about 40% gases and 60% solid residues, with the solids primarily manifesting as a white smoke. Chinese craftsmen also gave these emerging weapons remarkably vivid names – “Flying Rats”, “Big Bees’ Nest”, “Ten-Thousand-Fire Flying-Sand Magic Bomb” – a sign of both ingenuity and awe at the destructive force this new technology unleashed.

A major turning point in the history of gunpowder came with the Mongol expansion during the Song dynasty. The prolonged sieges of Xiangyang (襄阳) and Fancheng (樊城) turned the approaches to the Yangtze River into a battleground where new military technologies were tested relentlessly. At the khanate’s request, the Mongols acquired powerful counterweight trebuchets known as Huihui Pao (回回炮), built with the expertise of Persian engineers. These engines hurled “thunder crash bombs” (zhen tian lei, 震天雷) – the first hand grenades made of a cast iron shell filled with gunpowder with a fuse – whose blasts, smoke, and fire placed enormous pressure on Song defences. In this way, a substance born from Chinese alchemical inquiry became a decisive element in the fall of the dynasty itself, as gunpowder weapons accelerated the Mongol conquest and helped pave the way for the rise of the Yuan.

Gunpowder in Europe: Myths, Rivalry, and Transmission

Photo by: www.caiguoqiang.com/projects

Gunpowder most likely reached Europe through the far-reaching networks of the Mongol Empire, carried by caravans, envoys, and soldiers moving across Eurasia under the stability of the Pax Mongolica. As this knowledge travelled westward along the Silk Road, passing through Central Asia and the Middle East, new narratives about its origins took shape. One of the most persistent was the legend of Berthold Schwarz – a Franciscan friar and alchemist originally from Freiburg im Breisgau in the 14th century – later credited with inventing explosives, though he was almost certainly a figure of popular imagination. European scholars also searched for early formulas in the works of Roger Bacon, the 13th-century English natural philosopher, though he appears only to have recorded a mixture long known before his lifetime.

Over the following centuries, Europe moved far ahead in the development of gunpowder weaponry. Craftsmen refined formulas and casting techniques, improving the design of cannons and muskets, while military leaders tested new ways of using firepower on the battlefield. Intense and constant interstate rivalry transformed military innovation into a sustained engine of technological progress. Through these pressures, European states gradually mastered the art of controlling gunpowder energy, shaping not only the nature of warfare but the political landscape of the continent itself.

How Gunpowder Shaped History

Gunpowder revolutionised warfare and redefined the dynamics of the battlefield. It was crucial in the formation of empires and contributed to fostering political stability, trade, and cultural flourishing.

The Transformation of Warfare Through Gunpowder

The arrival of gunpowder reshaped warfare in fundamental ways. Fortress walls that had long defined the limits of siege strategy could now be breached, as artillery – particularly early cannons – reduced stone bastions to rubble and forced military engineers to rethink defensive architecture. At the same time, muskets and other firearms spread quickly through armies. Even when handled by soldiers with limited training, they delivered a level of force that challenged the dominance of elite troops armed with pikes and sabres. Firearms shifted the balance of power on the battlefield and redefined the terms of military organisation.

The Rise of the Gunpowder Empires

Gunpowder also shaped the emergence of the so-called gunpowder empires – the Ottoman Empire, including modern-day Turkey; Safavid Empire in Persia, modern-day Iran; and the Mughal Empire in India – where mastery of firearms became a central component of imperial strength. Through the disciplined use of artillery and muskets, these empires established themselves as major regional powers whose influence extended across large parts of Eurasia.

Each state integrated gunpowder technology into its military institutions.

- The Ottomans deployed heavy cannons capable of breaking the fortifications of Constantinople (now Istanbul) in 1453.

- The Safavids built a professional corps of musketeers – the tofangchi – who received regular pay and formed a key part of the army.

- In South Asia, Babur – a descendant of Timur, also known as Tamerlane, and Genghis Khan – secured Mughal rule after the First Battle of Panipat in 1526, where his forces made decisive use of artillery and firearms against the Lodi Empire. It marked the beginning of Mughal rule in India.

In these empires, gunpowder linked military effectiveness with political authority, helping to sustain stable rule and shape the geopolitical order of their time.

The Emergence of Centralised States in the Gunpowder Era

As the use of firearms expanded, around the 16th to the 18th centuries, monarchs grew less dependent on local nobles and their private retinues. Gunpowder weapons allowed rulers to assert more direct control: they could suppress rebellions, project force beyond traditional borders, and maintain armies that answered to the central state. Military successes supported by gunpowder often reinforced political stability, encouraged trade, and helped create conditions in which art and culture could flourish. In this way, control over firearms became one of the factors that strengthened emerging centralised states during the gunpowder era.

Gunpowder in China’s Culture Today

Gunpowder has profoundly shaped Chinese culture, particularly through the craft of fireworks, which is bound to both celebration and ritual. Its lasting presence underscores the delicate balance between tradition and modernity in contemporary society.

China’s Traditional Fireworks Craft and Intangible Cultural Heritage

Fireworks and firecrackers continue to play a vivid role in Chinese life, and many of the techniques used to make them are recognised on China’s National Intangible Cultural Heritage List. Across several provinces, traditional workshops still handcraft single-burst, double-burst, and multi-stage firecrackers with varied proportions of ingredients, with entire family lineages preserving the craft across generations.

One notable community is Nanzhangjing Village (南张井村) near Shijiazhuang (石家庄市) in Hebei Province, where residents create nearly 120 varieties of fireworks and firecrackers. Among them are Tiger Fire (老虎火), Rising Fire (起火), Pot Fire (锅子火), Umbrella Fire (伞火), Three Kingdoms Story Fire (三国故事火), Old Pole Fire (老杆火), and many others.

The process relies on carbonised willow wood, sprayed with alcohol, ground on a stone mill, and mixed with sulphur and saltpetre – a method that has appeared in local records for centuries. Within these communities, carefully measured proportions and consistent production techniques are believed to make the fireworks safer to use, reflecting not only technical precision but long-standing local expertise. For the artisans who still shape these mixtures by hand, pyrotechnics are more than a profession: they represent identity, lineage, and a living link to the early alchemical experiments that first unlocked the power of gunpowder.

Fireworks Traditions in China’s Festivals and Rituals

In contemporary China, fireworks remain part of a symbolic language that marks key moments of communal life. During Chinese New Year, the sharp cracks of firecrackers are traditionally said to drive away harmful spirits and “awaken” good fortune for the coming year. In rural areas, long red garlands of firecrackers are still lit in front of homes as signs of protection and prosperity, while cities host large-scale pyrotechnic displays as part of their official celebrations.

Fireworks also illuminate the final night of the Lantern Festival, when streets glow with thousands of lights and elaborate multi-stage pyrotechnic structures create effects known as “falling golden threads”, “meteor showers”, or “blooming spheres”. Increasingly, drone shows join these displays, forming dynamic images in the sky and blending ancient spectacle with modern technology. In temple rituals, firecrackers continue to mark the start of processions, highlight important moments in ceremonies, and serve as offerings of respect to the deities.

Gunpowder remains woven into China’s cultural landscape – not only as a historic invention, but as a shared expression of collective memory. Festival fireworks, the meticulous skills preserved in rural workshops, and the ritual use of pyrotechnics all show how the fiery energy of gunpowder continues to connect one generation to the next. Even as the world changes rapidly, these traditions help maintain continuity, grounding local communities in practices that have endured for centuries.

Where to Explore China’s Gunpowder Legacy?

China’s long heritage of gunpowder innovations is firmly rooted in its cultural landscape, offering many ways to explore its applications across contemporary life.

China’s Living Gunpowder Legacy: Cities, Museums, and Art

Traces of China’s gunpowder heritage appear across the country – in coastal cities of the south, in inland provinces, and in the historic landscapes once shaped by the Silk Road. A natural starting point is Liuyang, in Hunan Province, widely recognised as the birthplace of Chinese fireworks. Here, traditional workshops continue long-standing production methods, and the Liuyang Fireworks Museum in Hunan Province offers a detailed look at the history and techniques of pyrotechnics. The city now hosts regular large-scale shows, drawing sizeable holiday crowds and showcasing the full visual range of contemporary Chinese fireworks culture.

To explore early gunpowder technology, several major institutions hold rare and significant artefacts. Museums such as the Zhejiang Provincial Museum, the Shaanxi History Museum in Xi’an, and the Great Wall Museum at Badaling display bronze and iron cannon barrels, powder chambers, explosive vessels, hand cannons, and replicas of Ming-dynasty grenades. These collections trace the evolution of gunpowder from its earliest weaponry to more complex designs.

For a broader look at military technology, the Military Museum of the Chinese People’s Revolution in Beijing presents an extensive array of ancient and modern arms – from early bombs and rockets to howitzers and anti-aircraft systems. Together, these exhibits offer a clear sense of how gunpowder contributed to China’s long trajectory of military engineering.

Gunpowder’s presence in modern Chinese art is perhaps most visible in the work of Cai Guo-Qiang, whose signature “gunpowder paintings” and large-scale installations reinterpret the material in a contemporary idiom. His works appear regularly in Shanghai, Beijing, and Macao, demonstrating how a historic substance can become an expressive tool for modern visual culture.

How to Buy and Safely Use Firecrackers in China

In the weeks leading up to major holidays, licensed seasonal stalls appear across Chinese cities, selling firecrackers, small pyrotechnic sets, and festive “family packs”. Buying fireworks from these vendors is part of the holiday atmosphere, and sellers often share advice on choosing appropriate items – especially for visitors unfamiliar with local customs.

The sale of fireworks in China is strictly regulated, so travellers should only purchase from officially licensed outlets. It is important to avoid underground sellers, including those operating through messaging apps without a valid licence as their sales are illegal and subject to legal penalties. In addition, their fireworks may not comply with safety standards.

For those wishing to experience the tradition firsthand, it is best to light firecrackers in the company of local residents. Many people, especially in older neighbourhoods and temple squares, are familiar with the practical details: choosing the right spot, setting the direction, keeping a safe distance, and stepping back at the proper moment after lighting the fuse. A brief explanation from someone experienced – sometimes as simple as counting a few seconds aloud – can make the experience both enjoyable and safe.

For travellers, this moment is more than sound and spectacle. It is a small communal ritual, shared with those around you, shaped by anticipation, rhythm, and a flash of light. And with guidance from locals, adherence to safety practices, and purchases made through licensed vendors, it becomes a memorable glimpse into China’s vibrant festive culture.

Gunpowder remains one of those Chinese inventions whose influence continued long after its earliest appearance. It shaped military practice, entered craft traditions, became part of festive rituals, and left its imprint on art. Today, attitudes toward gunpowder are shifting: in a number of Chinese cities, fireworks are restricted or banned because of concerns about air quality, public safety, and the environment. Even so, the cultural memory has not disappeared. Holiday firecrackers still crackle through winter streets, small workshops continue to teach old techniques, museums preserve early weapons and pyrotechnic tools, and contemporary artists experiment with gunpowder as a medium – reminders that this ancient discovery remains woven into China’s modern cultural landscape.