China ranks first worldwide for the number of elements recognised on UNESCO’s list of Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity. This diverse collection of 44 el reflects living traditions that embody the country’s deep-rooted knowledge and cultural variety. Rituals, food customs, martial arts, and traditional medicine practices passed down through generations all contribute to a shared cultural identity. These traditions connect past and present, reinforcing the bond between modern Chinese society and its ancestors. It is this continuity that makes certain practices and expressions worthy of recognition as UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH).

China’s UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage: The Complete List of Traditions

The UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage was adopted in October 2003, and in August 2004, China became one of the first countries to ratify it. Since then, China has developed a large-scale system to study, document, and transmit its cultural traditions, combining national programmes with local community initiatives.

To be recognised as UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage, a tradition must be an essential part of community life, maintain generational continuity, and remain relevant in a modern context. Its significance for cultural identity, contribution to diverse forms of expression, and the consistency of efforts to preserve and transmit it are key criteria for evaluation.

Below is the list of China’s UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage elements, reflecting the country’s rich and multifaceted cultural memory across various aspects of life:

2024:

- Qiang New Year festival

- Spring festival, social practices of the Chinese people in celebration of traditional new year

- Traditional design and practices for building Chinese wooden arch bridges

- Traditional Li textile techniques: spinning, dyeing, weaving and embroidering

2022:

- Traditional tea processing techniques and associated social practices in China

2020:

- Ong Chun/Wangchuan/Wangkang ceremony, rituals and related practices for maintaining the sustainable connection between man and the ocean

- Taijiquan

2018:

- Lum medicinal bathing of Sowa Rigpa, knowledge and practices concerning life, health and illness prevention and treatment among the Tibetan people in China

2016:

- The Twenty-Four Solar Terms, knowledge in China of time and practices developed through observation of the sun’s annual motion

2013:

- Chinese Zhusuan, knowledge and practices of mathematical calculation through the abacus

2012:

- Strategy for training coming generations of Fujian puppetry practitioners

2011:

- Hezhen Yimakan storytelling

- Chinese shadow puppetry

2010:

- Meshrep

- Watertight-bulkhead technology of Chinese junks

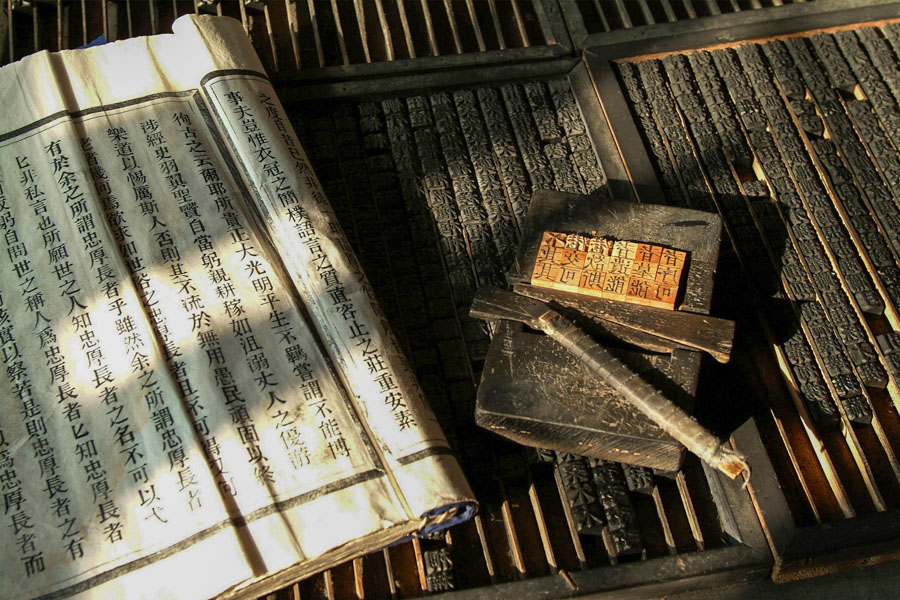

- Wooden movable-type printing of China

- Acupuncture and moxibustion of traditional Chinese medicine

- Peking opera

2009:

- Art of Chinese seal engraving

- China engraved block printing technique

- Chinese calligraphy

- Chinese paper-cut

- Chinese traditional architectural craftsmanship for timber-framed structures

- Craftsmanship of Nanjing Yunjin brocade

- Dragon Boat festival

- Farmers’ dance of China’s Korean ethnic group

- Gesar epic tradition

- Grand song of the Dong ethnic group

- Hua’er

- Manas

- Mazu belief and customs

- Mongolian art of singing, Khoomei

- Nanyin

- Regong arts

- Sericulture and silk craftsmanship of China

- Tibetan opera

- Traditional firing technology of Longquan celadon

- Traditional handicrafts of making Xuan paper

- Xi’an wind and percussion ensemble

- Yueju opera

2008:

- Guqin and its music

- Kun Qu opera

- Urtiin Duu, traditional folk long song

- Uyghur Muqam of Xinjiang

Most Endangered ICH of China: Four Traditions in Urgent Need of Safeguarding

Some traditions are vulnerable to the passage of time. Their bearers are dwindling in number, and ancient rituals, songs, and crafts are gradually disappearing along with those who still remember their meaning and sound. This is why UNESCO identifies elements that require urgent protection: their preservation is not only a matter of cultural memory but also an opportunity for future generations to inherit the history of their country.

Hezhen Yimakan storytelling

The Hezhen people, who live in northeastern China, have oral epic narratives called Yimakan – poetry and prose that tell of tribal alliances, battles with monsters and spirits, and the lives of hunters and fishermen. In these oral forms of storytelling, speech alternates with singing, and performers change their intonation to convey the voices of the characters and the development of the plot. Since ancient times, this skill has been passed down from mentor to student within the family, but today, training is also open to members of other communities. Since the Hezhen people have no written language, Yimakan plays a key role in preserving their native language, religion, beliefs, and customs.

But with the loss of their native language, which is now known only to the elders, the very existence of the tradition is threatened. In 2026, only five masters were capable of performing this art, and with the passing of the older generations, the living thread connecting the Hezhen people to their cultural roots is disappearing. This is why the Yimakan storytelling tradition is being promoted at the local level, and enthusiasts from other regions of the country can join in this ancient tradition.

Meshrep

The Uyghur people, who live in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, have created a unique type of public gathering called Meshrep. This event combines music, dance, drama, games, and feasting into a vibrant tapestry of community life. Such group gatherings served as both a theater and a “people's court”, as well as a platform for regulating order, discussing topics important to the community, and strengthening moral foundations. The tradition was passed down within the clan or neighbourhood: older participants introduced young people to the norms of behaviour and taught them games, songs, and dances.

However, in the modern world, the migration of young people to cities and the influence of mass culture have weakened the practice and reduced the number of practitioners. In order to increase the number of representative members of the community, financial support is provided, training seminars are held, and venues for gathering participants in the traditional Meshrep practice are being renovated. These measures will hopefully help ensure the continuity of this tradition within the Uyghur community.

Watertight Bulkhead Technology of Chinese Junks

A rare craft has been preserved on the coast of Fujian Province: the technique of watertight bulkheads for Chinese junks. This technology allows the hull of a ship to be divided into separate watertight compartments so that if one of them floods, the others continue to keep the ship afloat. Chinese junks are mainly built from pine and fir and are assembled using traditional carpentry tools. They are built using key technologies such as tongue-and-groove joints, and the seams are securely sealed with lime and tung oil. This art has mainly been passed down orally from generation to generation, from master to apprentice and between family members.

In the past, the finished junk was launched with a ceremony dedicated to safe sailing, during which the community offered thanks to the sea and prayed for safety and good fortune. Today, with steel ships replacing wooden ones, there are fewer and fewer practitioners of this technology, and in 2026, only three experts could assert complete mastery of this technology. Costs are rising and interest among the younger generation is waning, which is why master craftsmen now receive subsidies to enable them to continue practising their profession. To attract public interest, two junk boat museums have been opened in Quanzhou and Shenhu, and specialised centres for training young people have been established in Jinjiang.

Wooden Movable Type Printing of China

On the eastern coast of Zhejiang Province, an almost extinct skill is being preserved: the traditional Chinese technique of printing with movable wooden letters. Each letter is carved from hardwood, inserted into a typesetting board; ink is applied to the protruding surfaces, and then prints are made on sheets of polished paper. The peculiarity and main difficulty of this art is that when creating letters, Chinese characters must be carved in mirror format so that when printed, the resulting text is displayed in its usual form. Most often, this technology is used to compile genealogical books of family clans. The finished brochures contain information about the ancestors of each family: how long they have lived on this land and what outstanding deeds have brought fame to their clan.

With the advent of digital printing, the number of craftsmen has decreased, and in 2026 only eleven people were engaged in the ancient technique of engraving family books, so without support, this craft is in danger of dying out. However, UNESCO's attention to this issue has led to the opening of the Printing Culture Village Exhibition Hall in Dongyuan Village, near the city of Rui'an. Here, visitors can learn about this ancient tradition and, if they wish, try their hand at this art.

Safeguarding Intangible Cultural Heritage in a Changing World

The preservation of elements on China’s UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage list is increasingly strained by the forces of modernisation and urbanisation. As rapid urban development reshapes daily life, many long-standing practices and crafts now face the prospect of disappearing altogether.

Impact of Modernisation and Urbanisation

The rapid growth of cities, infrastructure, and services is changing the face of everyday life. Traditions that have existed for centuries in provincial communities are now on the verge of disappearing in a matter of decades. People are moving from traditional dwellings to skyscrapers, craft workshops are giving way to factories, and rituals that once shaped village life are fading into the background. In China, the swift pace of urbanisation is creating a gap between generations: young people leave their family homes, and their elderly relatives no longer have anyone nearby to whom they can pass on the knowledge inherited from their ancestors.

One example of a tradition that has come under pressure in this era of rapid change is traditional design and practices for building Chinese wooden arch bridges. This technique, common in Fujian and Zhejiang provinces, relies on joining wooden elements without nails or metal. Today, a shortage of wood and a lack of suitable construction sites pose the main challenges, and the number of craftsmen skilled in this art continues to decline. In response, educational centres and apprenticeship programmes are being established, and the restoration of surviving bridges is becoming a way to keep the tradition alive and introduce these skills to new generations.

Loss of Skilled Artisans and Practitioners

The loss of skilled craftsmen and bearers of traditional techniques is one of the major threats to China’s intangible cultural heritage. Many practices require not only technical knowledge but also hands-on experience gained through years of working alongside a master. When apprenticeship systems fade and younger generations pursue careers in the cities, the chain of transmission breaks. As a result, the direct connection between experienced artisans and potential apprentices weakens, and certain techniques become rare sights in a rapidly modernising world.

This is especially evident in traditions included in national and international heritage lists. One of them is traditional Li textile techniques on Hainan Island – a craft in which each stage, from spinning yarn to embroidering intricate patterns, is done entirely by hand and requires exceptional skill and attention to detail. Only about 1,000 people, mostly from the older generation, continue to practise this technique, so involving young artisans has become essential to ensuring its future.

China’s Evolving Approaches to Intangible Cultural Heritage Protection

Measures to protect intangible cultural heritage in China are becoming increasingly systematic. Key elements include legislation, educational initiatives, and cultural-economic models that strengthen the viability of traditions. The Intangible Cultural Heritage Law of the People's Republic of China is already in force, as are regional regulations designed to ensure the transmission of knowledge and skills.

The development of learning centres in local communities plays an important role. UNESCO workshops have fostered a network where young people and masters exchange experiences and create joint projects. For example, in the 1980s, the decline in young people learning the art of Fujian puppetry was significant due to socio-economic changes. However, measures supporting this tradition from 2008 to 2020, such as the creation of educational centres and performance venues, successfully reversed the trend and attracted new masters.

Thus, the safeguarding strategy combines legal protection, infrastructure development, educational support, and community participation, paving the way for the transmission of traditions to new generations and the strengthening of cultural capital at the local level.

Additionally, state support, local community involvement, and international cooperation are crucial. National exhibitions, such as China’s First National Intangible Cultural Heritage Exhibition held in Huzhou (Zhejiang Province), presented more than 100 cultural heritage items from 11 provinces and autonomous regions. The Beijing International Week of Intangible Cultural Heritage in October 2025 involved participants from 61 countries, highlighting the importance of such events.

Work at the community level remains vital, with platforms for traditional crafts and training programmes for young heirs established in villages and ethnic areas. Such initiatives strengthen the bond between generations and make cultural practices an important part of community life. One of the key measures was the creation of specialised workshops where artisans, together with young apprentices, practise traditional crafts, receive support, and become part of the local economy. Currently, about 11,000 workshops are operating in China, 4,300 of which are located directly in villages, ensuring traditional craft techniques and local production can be preserved without disrupting the communities’ traditional way of life.

In November 2025, the Beijing Municipal Bureau of Culture and Tourism released its inaugural list of Intangible Cultural Heritage Workshops, featuring 25 entities dedicated to traditional crafts, such as Beijing Gongmei Group and the Qiaoniang Handicraft Development Center. These workshops blend heritage with modern life, offering experiential zones, study programmes, and themed dining, allowing guests to engage with traditional craftsmanship.

In addition, international cooperation and knowledge exchange are developing, evidenced by the International Training Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacific Region (CRIHAP) in Beijing, which hosts joint training seminars for China and neighbouring countries. The Dunhuang Forum in Gansu Province brought together experts from more than ten countries to discuss new approaches to preserving traditions.

China's current policy on intangible cultural heritage focuses on keeping traditions alive, with government initiatives, community participation, and international cooperation forming a cohesive system that not only protects ancient crafts, rituals, and arts but also incorporates them into modern life. This reflects the belief that cultural heritage is a source of sustainable development, uniting generations and creating space for mutual understanding in the world.

Looking ahead, emphasis will be placed on digitally documenting traditions, creating interactive museums, and expanding educational programmes to make heritage accessible to young people. The gradual convergence of technology and traditional knowledge paves the way for the preservation of intangible culture as a living and evolving part of modern China.