The Cultural Revolution in China (1966–1976) was a political movement initiated by Mao Zedong, who was Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the leader of China. Mao Zedong Thought, or Maoism, is a form of Marxism-Leninism tailored to China’s specific circumstances. Mao's vision was shaped by a complex geopolitical context, ideological beliefs, and a desire to restore China’s strength as a unified nation that could assert itself proudly on the global stage.

This period marked a profound turning point that reshaped the foundations of the country’s cultural life. Art, literature, education, traditional customs and aesthetic values were subjected to strict regulations. Traditional art forms and classical heritage were dismissed as remnants of the past, while posters were employed as tools to convey new ideals. Revolutionary operas and large-scale mass performances emerged as new genres designed to support socialist ideology and foster a collective national identity.

The impact of the Cultural Revolution did not end in 1976. Its consequences continue to resonate in China’s artistic practices and cultural memory, reflected in ongoing discussions about the losses, disruptions, and transformations that followed. This guide explores how the experience of the Cultural Revolution modified the trajectory of Chinese art and how its legacy continues to influence the country’s contemporary cultural landscape.

Culture and Art during the Chinese Cultural Revolution

During the Cultural Revolution, art and artistic practices became closely intertwined with the ideological and social priorities of the time. This connection defined the era’s approach to traditional heritage and influenced new forms of collective artistic expression.

Reinterpreting Tradition and Cultural Heritage

The policies of the Cultural Revolution aimed to reshape attitudes towards traditional heritage and its role in modern society. Central to this effort was the concept of the Four Olds (四旧), which referred to old ideas, culture, customs, and habits of mind that were seen as inextricably linked to social structures of previous eras.

This perspective on the past established a new framework of cultural reference points for the generation that grew up after 1949, when the People’s Republic of China was founded. Classical Tang dynasty poetry, rituals of ancestor worship, and Confucian ethics were no longer viewed as central cultural elements. Instead, history was reinterpreted as a time characterised by social inequality and obsolete beliefs, reinforcing the perceived necessity for cultural renewal within the revolutionary context.

Transformation of Arts and Collective Identity

This shift led to a reassessment of the role of traditional art forms within public life. Peking opera, folk theatre, cinema, and music were increasingly interpreted through the lens of the ideological objectives of the period. Many traditional genres were largely replaced by new socialist themes, formats and genres that received official endorsement.

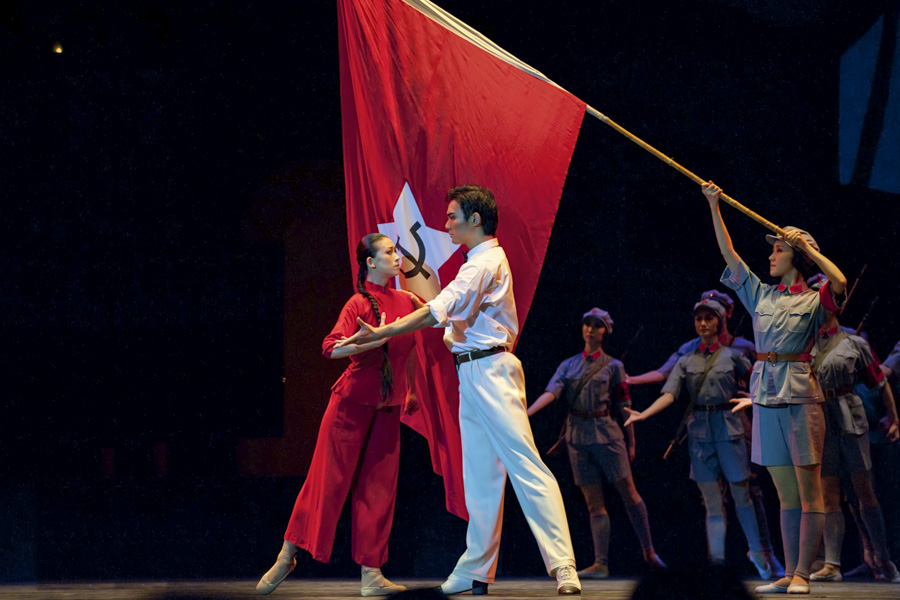

Artworks that emerged during this time prominently featured heroism, collective action, and revolution. Notable examples include the ballet The Red Detachment of Women (红色娘子军 Hongse Niangzijun) and the opera Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy (智取威虎山 Zhiqu Weihushan), both of which became essential elements of the official cultural canon of the era.

Simultaneously, the artistic landscape became filled with imagery reflecting revolutionary ideals and concepts of collective identity. Music, theatre, dance, and cinema were actively utilised as tools for social and cultural education, emphasising themes of heroism, devotion to the common cause, and the pivotal role of the working class. Art was seen as a crucial means for shaping values and social norms within the framework of state cultural policy.

The Red Guards, youth organisations established to actively participate in the political campaigns of the era, played a significant role in these cultural transformations. Their actions were instrumental in determining which forms of culture and art were considered acceptable and received public attention. As a consequence, artistic practices became increasingly confined to standardised imagery and collective models, effectively sidelining personal style and individual interpretation.

Shifts in Artistic Expression and Cultural Perception

As a result, artistic expression experienced profound changes during this period. Collective imagery and standardised narrative frameworks emerged as dominant forces, with art becoming increasingly aligned with the objectives of cultural policy and public education. These shifts left a lasting imprint on the evolution of Chinese art and influenced the perception of cultural heritage among generations who came of age during and after the Cultural Revolution.

Lasting Changes of the Chinese Cultural Revolution in Culture and Art

Following the conclusion of the Cultural Revolution, Chinese cultural policy and artistic practice gradually entered a phase of reassessment. In the decades that followed, this led to a renewed interest in traditional forms, their reinterpretation within contemporary art, and artists’ engagement with the experience of the recent past.

Revival of Traditional Culture in Post-Reform China

After the 1970s, set against the backdrop of economic reforms and a policy of openness, China experienced a gradual revival of interest in traditional art forms and cultural practices that had previously been sidelined in official cultural discourse. Classical painting and calligraphy were once again taught and practised, crafts and folk festivals were revived, and traditional culture steadily re-emerged in the public and artistic spheres as a vital element of national identity.

This process did not simply represent a return to the past; rather, it was a reworking of historical forms within the social and artistic conditions of the post-reform era. Many artists and scholars began to engage with traditional artistic codes, striving to integrate them into contemporary cultural practices while initiating an ongoing dialogue with the modern world.

Integration of Historical Styles into Contemporary Art

Photos source: www.phillips.com

In the post-reform period, many Chinese artists began to engage with traditional visual forms in innovative ways, viewing them as a resource for fresh interpretation. Calligraphy, classical painting, hieroglyphic writing, and traditional materials were increasingly used as vehicles for creative reflection and philosophical exploration.

A notable example is the work of Xu Bing (徐冰). His project Book from the Sky (天书 Tian Shu) mimics the canonical appearance of classical printed texts, yet is composed entirely of invented characters. This work references the tradition of written culture while simultaneously challenging concepts of meaning, textual authority, and cultural memory.

Through such practices, historical forms cease to function as a static legacy and instead emerge as an active artistic language – one capable of engaging with contemporary concerns.

Since the 1990s, Chinese artists have increasingly interacted with the global art scene through contemporary artistic practices. Many explore themes of memory, personal and collective experience, and the legacy of the Cultural Revolution alongside the broader social transformations that followed.

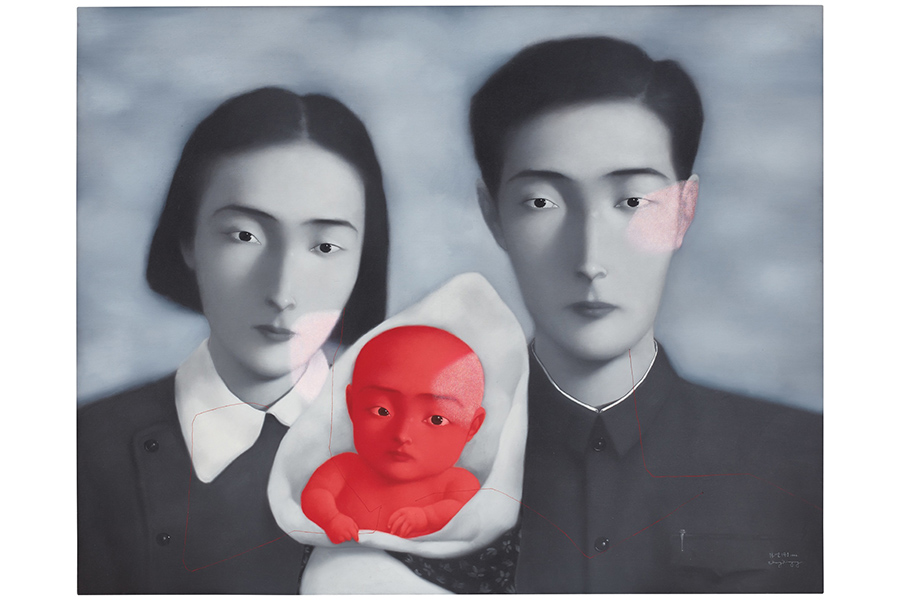

The work of Zhang Xiaogang (张晓刚), a Chinese symbolist and surrealist painter – particularly the series Bloodline: Big Family (血缘:大家庭 Xueyuan: Da Jiating) – draws on visual motifs derived from official portrait photography of the socialist era. Images of depersonalised family figures serve as metaphors for collective memory, diminished individuality, and the emotional distance shaped by historical experience.

Social and Cultural Impact of the Chinese Cultural Revolution

The Cultural Revolution was a formative period in Chinese society, significantly shaping attitudes towards tradition and moral values. Its consequences continue to resonate in public life and cultural discourse in contemporary China.

Revival of Confucian Thought in Post-Cultural Revolution Society

Following the Cultural Revolution, Chinese society gradually revised its stance towards philosophical and moral traditions that had previously been dismissed as relics of the past. A clear indication of this shift was the increase of interest in Confucian thought and its modern reinterpretations. Beginning in the 1980s, a broad revival of engagement with Confucian heritage took shape – a movement that, by the 1990s, became known as Traditional Chinese Studies (guoxue, 国学) and encompassed the study of classical philosophy, history, art and literature. This trend became embedded in official education policy and facilitated the reintroduction of Confucian texts into school and university curricula.

Alongside this, educational and research institutions began organising lectures, courses, and public seminars focused on Confucian ethics, moral principles, and their relevance to contemporary society. Simultaneously, the state concept of governing the country through moral guidance (以德治国) highlighted the ongoing significance of traditional values in promoting social harmony and shaping ethical norms in modern China.

Tradition and Modernisation in Contemporary China: Ongoing Social Debates

Memories of the Cultural Revolution continue to inspire extensive discussions about balancing the preservation of traditional values with the processes of modernisation. One illustration of this dialogue is the annual World Conference on China Studies held in Shanghai, which gathers hundreds of experts. This conference aims at fostering a wider agreement on advancing Sinology and encouraging ongoing cultural exchanges between China and the rest of the world.

At both national and international policy levels, debates also focus on China’s current development trajectory, stressing the need to reconcile inherited values with innovation. The Understanding China Conference in Guangzhou, for instance – attended by global politicians, scholars, and representatives from international organisations – addresses issues of modernisation within a broad socio-cultural framework and encourages the exchange of perspectives on the role of historical heritage in contemporary development.

These discussions extend beyond academic circles into everyday life, shaping attitudes towards lifestyle, family traditions, local customs, and shared values. Ongoing debates about how to align technological advancement with respect for cultural heritage reflect a broader search for sustainable models of development – ones in which the past is not discarded but integrated into an active and evolving conversation about the future.

UNESCO and the Preservation of Intangible Cultural Heritage and World Heritage in China

International cooperation in the protection of intangible cultural heritage (ICH) and World Heritage has become a significant aspect of China’s cultural policy. Through its collaboration with UNESCO, China ranks among the global leaders in the number of recognised elements, boasting 44 ICH items and 60 properties inscribed on the China World Heritage list. This highlights their significance not only for the nation itself but also for the broader international community. Such global recognition reinforces interest in the traditions of smaller cultural groups and supports their continued transmission within local communities. Moreover, landmarks on the World Heritage list often generate significant interest, which in turn leads to increased funding, tourist visits and resources for their maintenance and preservation. This ensures that these sites are protected for future generations.

Reevaluating Cultural Resilience After the Chinese Cultural Revolution

Finally, according to numerous scholars and social observers, the experience of the Cultural Revolution prompted a reevaluation of the role of heritage and enduring cultural reference points in Chinese society. Efforts to eliminate traditional forms and practices ultimately revealed their remarkable resilience and capacity to retain meaning despite profound historical upheaval. This realisation has fostered growing interest both within China and beyond its borders, where Chinese traditions continue to resonate with diverse cultural audiences around the world.

Cultural Revolution Landmarks and Artworks in China

The traces of the Cultural Revolution can still be read and observed in Chinese architecture, museum exhibitions, and the visual language of the era.

One of the most important sites associated with this period is Tiananmen Square (天安门广场) in Beijing, built in 1417, adjacent to the Forbidden City to the north. On October 1, 1949, Mao Zedong proclaimed the People's Republic of China from the walls of the Imperial City. It always served as the stage for mass gatherings, political campaigns, and public celebrations, shaping the visual and symbolic language of the era. Today, the square remains China’s primary public space and a defining feature of Beijing’s historical landscape.

Within Tiananmen Square stands the Mausoleum of Mao Zedong, also known as the Chairman Mao Memorial Hall (毛主席纪念堂), which opened in 1977, after his death in 1976. The Mausoleum's design aims to blend traditional Chinese aesthetics while avoiding references to imperial tombs. Gu Mu, a prominent architect, oversaw its design to ensure it celebrated revolutionary achievements and utilised materials sourced from all regions of China. It continues to function as an official memorial and forms part of the broader ensemble of Tiananmen Square.

Also nearby is the National Museum of China (中国国家博物馆), situated directly to the east of Tiananmen Square. Its permanent and temporary exhibitions feature a wealth of material on the history of the People’s Republic of China and the Cultural Revolution. The visual aesthetics of this era are especially apparent in works created in the style of socialist realism. One of the most recognisable pieces is Dong Xiwen’s The Founding Ceremony of the Nation (1953), an oil painting on canvas, which stands as the defining example of official art of the mid-20th century.

In Front of Tiananmen is a 1964 oil on canvas by the Chinese artist Sun Zixi, measuring approximately 155 × 285 cm. The painting depicts groups of people at Tiananmen Square, often shown taking photographs in front of the famous site, and is considered one of Sun’s important works held by state museums.

Photo source: www.liveauctioneers.com

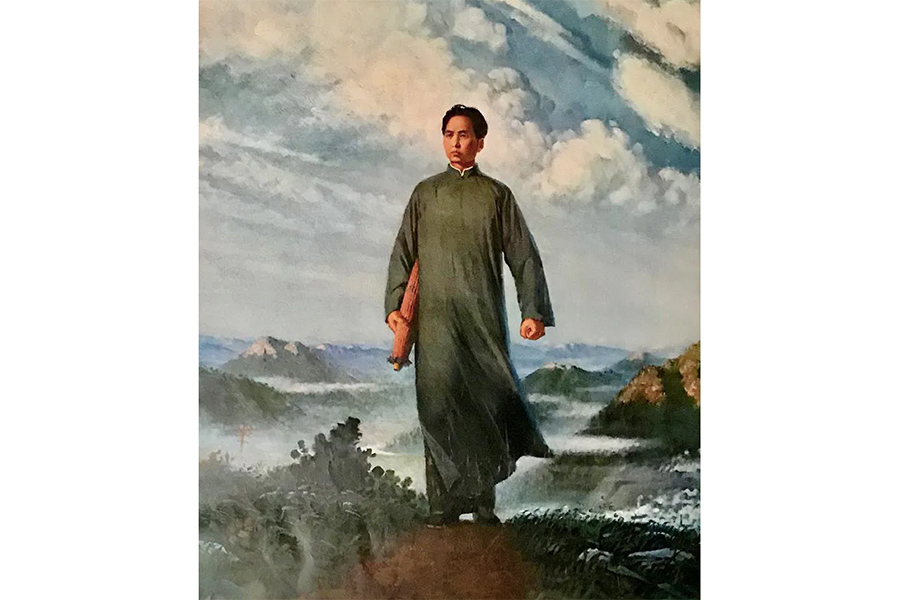

Perhaps the most iconic image of the period is Chairman Mao Goes to Anyuan (毛主席去安源), created in 1967. It portrays a young Mao Zedong walking towards the Anyuan coal mines to mobilise a revolutionary workers’ movement. Rendered with restraint and symbolism, the figure appears in motion against a simplified landscape, stripped of everyday detail, which lends the scene a solemn, emblematic tone. Widely reproduced as posters and prints, the image became one of the most recognisable visual symbols of the Cultural Revolution. Today, it can be viewed at the Anyuan Miners’ Strike Memorial Hall (安源路矿工人运动纪念馆), in the city of Pingxiang, Jiangxi Province, alongside sculptures of miners, historical photographs, and period newspapers.

Through documents, posters, paintings, and everyday objects, museum collections reveal how the ideological ideas of the time permeated visual culture and daily life.

Alongside painting, mass culture also played a powerful role in shaping the atmosphere of the period. One striking example is the song The East Is Red (东方红), written in the 1930s and widely performed at mass events during the Cultural Revolution. Regularly broadcast on radio and serving as the de facto national anthem at the time, it became an inseparable part of the era’s cultural soundscape.

When viewed collectively, these sites and works illustrate how the ideas of the Cultural Revolution influenced public life and shaped perceptions of the world in China during that period.